Erosion undermines historic riverfront

February 21, 2012

Erosion along the Cape Fear River is prompting concerns about damage to properties between Old Inlet and the N.C. State Port at Wilmington, including the Brunswick Town/Fort Anderson State Historic Site and Orton Plantation.

Efforts to increase the size of ships able to traverse the 28 miles between Bald Head Island and the state port docks opposite Eagles Island may have contributed to the erosion of properties along the riverfront, according to some property owners and watchdog groups.

Properties impacted range from Old Inlet beaches on Bald Head Island to the colonial port of entry north of Military Ocean Terminal Sunny Point and Orton Plantation. Concerns have been mounting about the effects of erosion since the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers deepened and widened the Cape Fear River navigation channel from 38 to 42 feet in 2004. At Brunswick Town, twelve miles south of Wilmington in Brunswick County, those concerns have taken on a new urgency in the last year.

“I think this is critical,” said Brenda Bryant, manager of Brunswick Town/Fort Anderson State Historic Site. “The erosion has been happening for a couple of years, but it has become very aggressive this past year. It has become a priority for this site.”

Bryant points to the dredging project that took place less than 200 yards from the riverbank as a possible cause of Brunswick’s disappearing shoreline.

“We know that the river channel was dredged within the past six or seven years,” said Bryant. “Evidently what came out of that was more damage to the rice fields at Orton, and we know Bald Head Island has a lawsuit about that same dredging project and the erosion they say it caused there. It really affects those of us who are close to the shipping channel, which is on the west side of the river.”

Jim McKee, a historical interpreter at Brunswick Town/Fort Anderson, has been working at the site since 2008. In that time, he has watched the shoreline, which was once a working waterfront during the colonial era, wash away each time a large ship passes by.

“The waterfront has eroded anywhere from 50-60 feet perpendicular to the shoreline in the four years since I began working here,” McKee said. “Depending on the area, it may be more or may be less.”

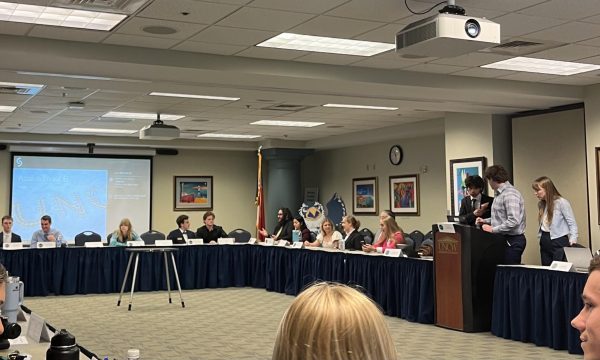

Before culpability can be assigned, evidence has to be gathered. Cape Fear River Watch, with help from UNCW scientists and equipment, is trying to gauge the effect of passing ships on the river’s shoreline.

At Brunswick Town, McKee has begun keeping data on the erosion problem, including photos and video that document the effects of passing river traffic. Using the same U.S. Geological Survey benchmark Dr. Stanley South used in 1960 to measure the waterfront during the site’s original archaeology, McKee has been able to establish exactly how much that erosion has claimed over time.

“When Dr. South took his measurements, the low tide mark from the USGS benchmark was 115 feet. High tide was 42 feet,” said McKee. “As of February 2012, the water was 2.5 feet past that benchmark. If you base your measurements on the low tide mark, and we’re three feet past what it was in 1960, then we’ve lost a total of 118 feet since Dr. South took his original measurements.”

Orton Plantation, just north of Brunswick Town/Fort Anderson, has suffered as bad or worse. Orton Point is the place where the shipping channel is closest to land between the bar at Old Inlet and Wilmington. Erosion there has prompted engineers working for owner Louis Moore Bacon to install rip-rap, a wall of loose stone that buffers against wave action, to save the earthen sea wall that protects the plantation’s rice fields. That may not be an option for Brunswick Town or other properties along the river.

Strict guidelines regulate what type of structures may be built along waterways in North Carolina. The process is governed by rules in the Coastal Area Management Act. Some structures, like the wall at Orton, were grandfathered in when the legislation was passed. Such is not the case with every property on the river. In the case of Brunswick Town/Fort Anderson, tight state budgets also become a factor.

“When you talk of money, you wonder where it’s going to come from,” Bryant said. “But I think as far as this goes, this is something critical. When the water is approaching Battery B (of Fort Anderson), you definitely want to do something before the waves are lapping at the foot of the historic fort’s earthworks. It’s almost at that stage.”

Kemp Burdette, executive director of Cape Fear River Watch, also suspects that shipping is the most likely erosion culprit.

“It’s two things,” said Burdette, “the wakes and water displacement caused by the ships, and the change in the channel profile from the dredging.”

Burdette said that as dredging is done, the riverbed around it gets correspondingly higher. In time, the channel profile, or angle of repose, of the embankment becomes too steep. When that happens, the top begins to slough off until a gentler angle is formed. That sloughed off material refills the shipping channel, necessitating new dredging.

The 2004 dredging project that deepened the Cape Fear River channel has allowed longer, heavier ships to make the trip to the N.C. State Port Facility at Wilmington. That means larger volumes of water are displaced when the ships pass in transit. According to the N.C. State Ports Authority, the largest ship calling at the Port of Wilmington since the dredging measures 965 feet in length. In total, 441 ships of various sizes made the trip to Wilmington and back again in 2011.

The result of all that moving water is an effect much like that of a tsunami, where water is sucked away from shorelines to fill the massive hole in the water created by the passing vessels. When the river re-establishes its equilibrium, the displaced water rushes back to shore. Burdette described the action on the shoreline as being like “water in a bathtub.” As the water sloshes back and forth, protective vegetation and soil is swept away.