These are not radical ideas: Sanders’ democratic socialism vs. the democratic establishment

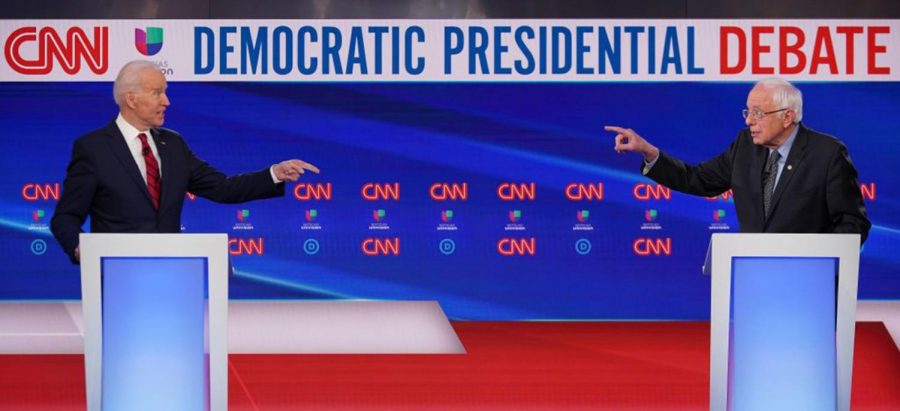

Mandel Ngan/AFP/TNS

Democratic presidential hopefuls former US vice president Joe Biden (left) and Senator Bernie Sanders point fingers at each other as they take part in the 11th Democratic Party 2020 presidential debate in a CNN Washington Bureau studio in Washington, DC on March 15, 2020.

As the world grapples with an unprecedented health and economic crisis, the Democratic Primary marches on. It remains a race between former Vice President, Joe Biden, and the self-described democratic socialist senator, Bernie Sanders.

The former has earned endorsements from nearly every past-primary contender and represents a retreat to a time before Trump’s immigration policy, the repeal of 95 environmental regulations and, of course, the continued effort to dismantle Obamacare. Bernie Sanders, however, represents a break from both the Trump and Obama years. In short, he advocates for the dismantling of the system that gave rise to Donald Trump in the first place—that is, a system that perpetuates corporate domination of politics and allows for the further consolidation of income and wealth in the elite class strata of the U.S.

Unfortunately, the dismantling of such a system is not only against Republican interests, but also Democratic Party interests. In recent interviews with the New York Times, Democratic leaders and super-delegates revealed their worries about a Sanders nomination and expressed concern over whether Sanders can beat Trump. They even went so far as to oppose supporting Sanders for the nomination even if he wins a plurality of voters.

Outside Democratic Party leadership, opposition to Sanders comes from mainstream media outlets, such as CNN, which recently ran a segment titled “Can Either the Coronavirus or Bernie Sanders be Stopped.” Much of this opposition is clearly tied to Sanders’ commitment to democratic socialism. To many individuals across both parties, and similar to perceptions of communism during the Red Scare era, socialism is virus-like: it infects innocent people and leads them to an un-American worldview.

Many long-time Democratic pundits have also vehemently attacked Sanders and democratic socialism more broadly. James Carville, a political strategist and media personality, recently branded Sanders as a communist and referred to his supporters as a cult. Similarly, Chris Mathews questioned what “type” of socialism Bernie Sanders truly represented and likened his vision to the communist dictatorships of the Soviet Union and Cuba that evoke past Cold War imagery. He even suggested that Sanders would have cheered public executions in Central Park if “the Reds” had taken over the country and captured Matthews himself.

Yet, it is not just the negative stigma of socialism that is weaponized against the Sanders campaign. Mainstream media has frequently embraced the narrative that Sanders’ supporters are aggressive and divisive, with the mass of Sanders’ online support often portrayed as “Bernie Bros”—a revival of the pejorative from 2016 that characterizes his base as primarily young boisterous men.

CHICAGO, ILLINOIS – MARCH 07: Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) arrives for a campaign rally in Grant Park on March 07, 2020 in Chicago, Illinois. The Illinois primary will be held on March 17.

Even after dropping out, fellow progressive Elizabeth Warren stated that she believes presidential candidates are responsible for the way their supporters behave both online and offline and added that Sanders’ online supporters are particularly nasty. Though there has been no empirical support for the claim that Sanders’ supporters are any more or less toxic than other campaign supporters, Sanders has condemned online bullying of any sort. Others such as Sanders’ campaign surrogate, Nina Turner, have pushed back on this narrative, arguing that other campaigns have been just as vile and aggressive, and she has led an online effort to draw attention to the many people of color who support Senator Sanders.

The resistance to Sanders from Democratic leadership as well as mainstream media leads to two questions: What is it about Sanders’ platform that invokes such passion as to ignite arguments around online “decency?” and What exactly is this platform of democratic socialism that is so feared by Democratic leadership and corporate media pundits?

Socialism is a messy concept. It maintains various connotations and remains both heralded and derided. On the one hand, it is attached to repressive regimes from Stalin to Castro. This, of course, sidelines the issue that many capitalist countries have also featured authoritarian rule and even dictatorship, such as Chile under General Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990) and contemporary Singapore. Russia under Putin also falls into this category. On the other hand, socialism is associated with the Nordic political-economic model, which involves a large social welfare state, a mixed (public/private) economy and widespread political democracy.

Socialism, in a broad definition, is an economic system centered on the public ownership of the means of production. The point of such a system is to emancipate laborers from the constraints of a capitalistic system in which one must sell their labor in order to procure a wage to then purchase the means of subsistence (i.e. food, shelter, clothing). Socialists argue that the relationship between workers and business owners is inherently unequal.

One of the major mechanisms through which business owners and executives profit is by suppressing worker wages. While many workers’ wages have failed to rise over the past several decades, CEO pay has skyrocketed; in fact, the CEO to worker wage ratio is currently 278 to 1.

Under socialism, citizens would work to decommodify many services and to eliminate many private businesses operated by corporate boards with motivations of profit. On the ground, though, some socialists have disagreed over the route towards this future society. Within the Soviet Union and its satellite states, for instance, state bureaucrats planned the production process.

This operation was far from democratic and involved little input from workers. Instead of state planning, many socialists, including Karl Marx himself, championed other forms of democratic control over the economy. This is one reason why folks like Bernie Sanders and the Democratic Socialist Party of America explicitly distinguish their vision as involving “democratic socialism.” In both politics and the economy, democratic socialists believe that people should govern their lives through their own decision-making.

Senator Bernie Sanders described what he personally meant by democratic socialism: “Now, we must take the next step forward and guarantee every man, woman and child in our country basic economic rights – the right to quality health care, the right to as much education as one needs to succeed in our society, the right to a good job that pays a living wage, the right to affordable housing, the right to a secure retirement, and the right to live in a clean environment… That is what I mean by democratic socialism”

In this speech, Sanders demonstrates his belief that we should decommodify some services and features within society such as health care and education, and he describes these services and features as basic economic rights. Yet, how might a democratic socialist economic model accomplish such objectives?

In some of his work, the late sociologist Erik Olin Wright sought to weigh in on how a democratic socialist economy might look. For him, it would consist of democratically governed and publicly owned firms both inside and outside the state. Outside the state, this looks like worker cooperatives, where decisions are made collectively by workers through a “one person, one vote” model. Inside the state, this looks like the public provision of, for instance, healthcare, childcare, education and energy. Of course, it is of the utmost importance that these changes reflect the interests of a majority of people and not just the richest Americans; that is why the “democratic” in democratic socialism is so important.

Bernie Sanders has issued scathing attacks against corporate interests in politics because this is precisely the way in which democracy is upended. If our electoral system was truly open and democratic, the Democratic Party might look a bit different. How is this so? Consider the exit polls in the primary thus far: in Texas and California, 53 percent of voters have a favorable opinion of socialism; in the first four primary states, over 50 percent of voters support a government healthcare plan for all.

It turns out that many people—after years of paying for private insurance—are tired of arguing with their profit-driven insurance companies about what procedure should be covered or what and who is “in-network.” They also may be voting in the interests of the 30 million people in the U.S. without healthcare.

It appears, then, that if Medicare-for-All was put to a widespread democratic vote, it might very well win at the ballot box. Instead, we have corporately funded politicians who block such efforts. Indeed, since Senator Joe Biden’s strong Super Tuesday results, stocks within the healthcare industry have boomed.

Yet, healthcare is only one part of Sanders’ platform. How does democratic socialism match up to some of the other features of his platform? In line with his advocacy for economic justice, Sanders champions tuition-free college, a federal jobs guarantee (many in healthcare, childhood education, and energy, housing for all, equitable funding for public schools, strong worker unions, worker-owned businesses and workplace democracy, that is, giving workers representation on corporate boards and distributing company stock to workers.

One can surely make the argument that many of these reforms lean more towards social democracy rather than democratic socialism. However, worker-owned businesses and “workplace democracy” actively place more power in the hands of workers and give them a share of ownership over the means of production. In doing so, they transfer decision-making powers away from elites and into the hands of workers. So, is this what the democratic establishment is afraid of? Does this sort of policy warrant accusations of authoritarian communism from media pundits?

It is clear to see that the Democratic establishment is indeed at odds with democratic socialism. As a result, we hear arguments that “Bernie is too radical; he will divide the party and Donald Trump will win again.” Yet, Bernie polls extremely well against Trump—often better than Biden.

Former Vice President Joe Biden, left, and Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) greet one another with an elbow bump before their debate on March 15, 2020 in the CNN studio in Washington, D.C.

More importantly, though, we should ask ourselves whether or not these ideas are truly radical. Is it out of line to demand fair pay and equal opportunities to a quality education? Is it radical to think there is a way for all Americans to have quality healthcare? Is it really far-fetched to imagine businesses governed democratically and workers remunerated adequately? And lastly, if democratic socialism is a threat, we should ask ourselves: whose way of life is it really threatening?

To a large portion of the Democratic Party, this “threat” sounds like a more democratic and egalitarian way forward, perhaps unsettling elite domination of both the political and economic spheres of life.