The fight to end hunger and homelessness in Wilmington

There’s a window at Vigilant Hope Roastery in downtown Wilmington that looks out onto S 16th St. A chair, small side table and windowsill lit by the afternoon sun provide a quaint nook within the cafe.

While some people see only a window in a corner, Marsel McFadden sees an escape.

“I start every morning here to get my mind right. And when I’m here, I’m not just a statistic,” says McFadden as she gazes out the sunlit window, rays illuminating her impassioned face.

Wilmington’s Northside, McFadden’s beloved home, is riddled with statistics that cause many to simply turn a blind eye: low income, elderly, teen pregnancies and people of color.

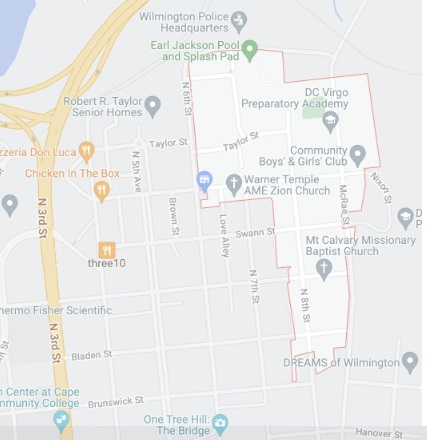

The Northside is what molded McFadden into the advocate she is today. It lies just east of the Cape Fear River, bordering downtown Wilmington. With its outline shaped like a key, the Northside is home to many well-known establishments, such as the DC Virgo Preparatory Academy, Community Boys’ and Girls’ Club and Mount Calvary Mission Baptist Church. The hardships plaguing this area of Wilmington include, but are not limited to, food insecurity, financial insecurity and gentrification.

Food insecurity in particular runs rampant through the Northside. A quality grocery store cannot be found within a mile radius in this area.

There hasn’t been one in thirty-five plus years.

In 2020, the USDA found that over 30% of the population in New Hanover County had low access to grocery stores. Areas in which obtaining fresh and quality food typically found at grocery stores is difficult are termed food deserts, and there are eight in Wilmington alone.

But what constitutes “quality food,” and why is it important in an everyday diet? Whole grains, vegetables, fruits, sufficient protein and healthy fats all fall into the broad definition of a healthy diet according to the National Library of Medicine. Consuming the recommended daily portions of each of these provides a plethora of health benefits, such as increased cardiovascular health, increased energy levels and maintaining a healthy body weight. Such benefits can even be broken down to the cellular level of health, which goes to show the importance of quality foods.

Grocery stores and supermarkets are the two prime locations to purchase fresh foods such as these. Convenience stores, however, do not carry such items. McFadden recalled an observation she had about the convenience store in her area. She said that a person could go to Food Lion and buy two cans of corn for $1.50, while the convenience store down the road sells the same thing for $4.00.

“I remember being young and just saying I wish we had a grocery store, like, when I get older and I hit the lottery I’m gonna build a grocery store over here. It was just one of those things that we never had,” said McFadden.

The Northside is a short fifteen-minute drive from UNCW’s campus. The difference between grocery store availability between these two locations is astounding. UNCW’s campus has a Lowes Foods, Trader Joe’s, Harris Teeter, Whole Foods Market, Food Lion, Lidl and Walmart Supercenter all within a two-mile radius.

If this one location can have seven grocery stores, why can’t the Northside have one?

Introducing the Northside Co-op and Frankie’s Outdoor Market. The Co-op, formally known as the Northside Food Cooperative, is the cornerstone to building a grocery store in the area, as reflected in their mission statement. Their goal is to end food deserts in the Wilmington area and provide food security for those in need. They also hope to bolster their area’s economy through their endeavors.

Frankie’s Outdoor Market is a branch of this initiative, with the goal of bringing quality foods into the area for purchase by residents at reasonable rates. Not only are fresh foods brought in, but artists, photographers and crafters come from across Wilmington to share their products with the community.

Behind Frankie’s Market is a gated area of land—the beginnings of a community garden. While it may not look like much, McFadden’s face beams with excitement and pride when asked about the garden.

About a month ago, the garden was simply a single pallet laid in the corner of a small plot of land that was overgrown with grass and littered with weeds. The transformation from April 7 to now is breathtaking.

“We have green peppers and tomato plants and blueberries, like the blueberries are starting to come up on the bushes! It’s so nice,” explains McFadden. “These things were ideas that were set in stone in the ground like seeds, you know? And they grew roots, and they started to grow out the ground, and now everything is blossoming.”

While the goal of the Co-op and Market is to end the food desert, they both share a core value that stands firm: community. This program would not be possible without the executive board, ambassadors, members, vendors and, most importantly, the residents. Residents are not only able to partake in the vendors that come, but they have the opportunity to take ownership of the community garden and play an active role in its cultivation. In McFadden’s words, “Community begets community.”

But this beautiful picture of community is being threatened. Food deserts walk hand-in-hand with low-income areas, which are ultimately subject to gentrification. The goal of gentrification is to uplift seemingly low-run areas to fit societal perceptions of “livable” and “appealing” neighborhoods. This includes business additions to the area, higher income families moving in and new, top-end housing construction. However, every process has negative effects. An increase in higher-income businesses and homes consequently leads to higher living expenses within the area. What happens to the people who can barely afford to live there in the first place? Companies pushing for positive outcomes through gentrification may seem promising, but the process itself pushes lower-income families out of their homes, leaving them unable to find sufficient housing.

Interestingly enough, the Northside has seen an increase in diversity due to gentrification. In 2017, about 7,500 residents lived in the Northside of Wilmington, with about 2,700 households and a population of 67.5% African American. The community was also mainly elders at this point in time. Now, the community has shifted in age, races, and incomes.

“I think that’s that makes food insecurity so universal…it doesn’t just affect certain groups of people; it can really affect anyone,” said Cierra Washington, the Strategic Partnership Coordinator for the Northside Co-op.

Washington’s statement furthers the notion that gentrification and food insecurity are not gender, race, age or income specific. These injustices can affect anyone, and gentrification is causing the groups to broaden.

A study conducted by the National Association of School Psychologists in 2018 concluded that gentrification acts as a catalyst leading to homelessness. While this research was mainly focused in Denver, Colorado, its principles can be applied elsewhere.

Furthermore, in 2021, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development conducted a point-in-time count of the homeless populations across the country. In the NC-506 area—which includes Wilmington/Brunswick County, New Hanover County and Pender Counties—a total population of 301 homeless persons was documented, ten of which were identified as chronically homeless. Chronic homelessness consists of two criteria: being homeless for at least a year (or repeatedly), and coping with a debilitating condition such as serious mental health issues, substance abuse and/or a disability of some sort.

New efforts to aid the homeless community have recently sprung up in Wilmington. In Wilmington alone, the total homeless population, including sheltered and unsheltered individuals, decreased by 44%. This can best be explained by the influx of financial support, such as stimulus checks and other forms of assistance, during peak pandemic season in 2020. This outcome, however, is temporary for an ever evolving, long-term issue.

A current endeavor to aid the homeless community in Wilmington is a project entitled “Eden Village.” Originating in Springfield, Missouri, Eden Village is a tiny-home community specifically for the chronically homeless. Their mission is “to build relationships and communities for our chronically homeless friends. We believe that the solution to poverty is dignity and that the solution to homelessness involves a home and a community.”

Shawn Hayes, one of the head contractors for Eden Village of Wilmington, fully believes the restoration of dignity is as critical as diminishing homelessness.

“Dignity is the solution to poverty,” said Hayes. “Did you see the home inside? We have a nice big front porch with rocking chairs; the details inside—crown molding—everything is tastefully and thoughtfully done. It’s not just thrown together; it’s a nice place that you can be proud of living in. That gives them a sense of dignity.”

Hayes further explained that the community is going to be gated with no foot traffic. Biometrically controlled gates will allow residents’ thumbprints to be their key into the community.

“The only people that are supposed to be in here are the people supposed to be in here,” said Hayes.

Eden Village of Wilmington will have a total of thirty-one tiny homes specifically designed to promote community. Residents will be able to get to know their neighbors better and develop deep and meaningful relationships. No one can better understand circumstances than a person that’s gone through the exact same situation. The bond that can be built from such a connection is a genuine and beautiful one.

There is a responsibility innately understood throughout society: it’s our job to create a community that is better for the next generation. Marsel is a mother of three and will stop at nothing to create a better world for her children.

“It’s our job to create a city full of opportunity, full of food, full of protection and love and community,” she said.

Awareness of these issues has been spread throughout the entirety of Wilmington through the local endeavors of Port City Community Church, specifically with an experience called “Encounter the City.”

“Encounter the City is an opportunity to go outside the walls and just go to different routes that we normally wouldn’t go and experience our communities in a whole different lens,” explained Javi Mendoza, a staff member at Port City, and the main proponent behind this tour. “It’s getting to know what’s happening in our communities and how they are involved, how they are partnering with organizations for whatever cause that may be: food security, housing crisis…”

Encounter the City consists of three main stops: Eden Village, Frankie’s Outdoor Market and Vigilant Hope Roastery. The main focus of the tour is to educate the public on the issues continuously occurring in town, many of which are a short drive away.

Frankie’s Outdoor Market is in need of ambassadors, vendors and members. Eden Village always takes volunteers to help cultivate their community garden. The same can be said for Frankie’s backyard garden, as it has just begun. People can also recommend the Encounter the City tour to individuals and organizations. Numerous other steps can be taken to finally end Wilmington’s hunger and homelessness.

Take ownership. Speak out. Make a difference.

When someone doesn’t encounter or see hardship and strife on a daily basis, it’s easy to live in a bubble and not notice anything outside of it. People are hungry, hopeless, scared, homeless and desperate for help right next door.

McFadden looks out at the parking lot, deep in thought with tears brimming in her eyes.

“I used to think why me? Why’d I have to go through this? Why’d this have to happen to me?” she said. “Now it’s like, why not me?”

So why not you?

“I understand the world is round,” McFadden explained. “So, it don’t change. Things don’t stop with me. It’s just round and it keeps happening, and it keeps happening, and it keeps happening, until someone gets the guts or the courage to want to make a difference and to stand firm on it.”

Heidi Wood • Apr 14, 2023 at 4:30 pm

Awesome article

Sabrina Garcia • Apr 14, 2023 at 3:26 pm

This is such a beautiful and inspiring article. As much as anyone I want to see the world succeed and grow together and the best way to do that is to lift each other up. Thank you Lindsey for this article.