Recognizing Native American Heritage Month: Who was here before us?

This is the 30th anniversary of government recognized Native American Heritage month and despite the civic rupture of 2020, we have found ourselves recognizing silenced voices and the history of their oppression.

With this, a new definition of the holiday Thanksgiving is emerging. As children, we learned that Thanksgiving is about the Native Americans and the Pilgrims gathering together to have a grand meal. However, history is catching up with us and we are realizing that it was not always breaking bread and smiles.

This year, you can commemorate Native American Heritage month by understanding the history of our very own UNC school system, which sits on purchased packages of indigenous land.

The Morrill Act in 1862, signed by President Abraham Lincoln, allowed federally owned land to be given to the states in order to sell and fund educational institutions.

The Morrill Act was created in order to benefit colleges across the country, provide education to promote scientific farming, produce skilled labor, foster technological innovation and improve civic knowledge.

Many universities across the southern US region gained funding in their early years from the sale of land through treaties with various Native American tribes. The UNC schools are among those universities, investing in Cherokee and Chickasaw land in what is now western Tennessee.

University of North Carolina at Wilmington (UNCW) is just one of the 52 U.S. universities that profited from the buying and selling of over 10 million acres of Indigenous land.

A High Country News research study conducted by Robert Lee and Tristan Ahtone, found that from 1818 to 1840, land sales profited an average of 34.6% of UNC’s annual budget.

Despite the Morrill Act stating that the money made from the buying and selling of this Indigenous land could be used only for universities, this Indian dispossession provided the federal government with land on which to build churches, bars, parking lots, billboards, restaurants, gas stations and a variety of different properties, creating opportunities for its expanding white citizens.

These grants from the Morrill Act became a substantial factor in providing public education to American children. State colleges funded by these grants brought higher education within the grasp of millions of students, which could not help but reshape the nation’s social and economic development.

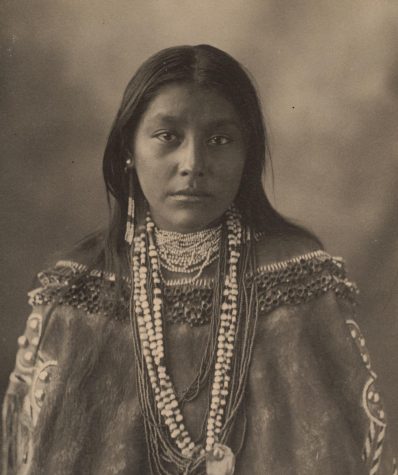

This federally owned land, however, was obtained through unratified treaties. Because the Native Americans at the time did not agree to these treaties that were just between the federal government and state governments, these treaties were not valid. Also, most Native Americans could not read or write English so they were not able to read these treaties and consent to them.

Land was the key to the Federal Government’s early involvement and this Indigenous land was the most readily available in the unopened continent. However, this land was only made “available” for purchase because the government had forced the removal of these Native American tribes onto often swampy and unfarmable reservations. While the universities developed a new and prosperous future for its state residents, displaced Native Americans suffered tremendously.

UNC was able to seize these Indigenous lands because of The Great Chickasaw Cession treaty signed in 1818. This formally allowed the UNC system to seize all Chickasaw territory in Tennessee. From this, UNC was able to bounce back financially well into the 19th century.

High Country News has located more than 99% of the land bought and sold under the Morrill Act, consisting of approximately 10.7 million acres taken from nearly 250 tribes.

According to the Morrill Act, all of the money made from the buying and selling of this Indigenous land must be used for a long period of time, to which has no end. This means that the funds from the Indigenous land still remain on university’s ledgers to this day. Approximately 12 states still possess unsold Morrill land which continue to build revenue for their universities.