REVIEW: ‘Six Degrees’ of Different Experiences

“Six Degrees of Separation,” a play by John Guare, can connect any one person to another by a short chain of four people. It can connect English department lecturer Kimberley Faxon-Hemingway to George Clooney (Hemingway’s brother, Nat Faxon, helped write the screenplay for “The Descendents” in which George Clooney starred) with just one degree of separation. It can also connect a young black man in the late 1980s to the elite of Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

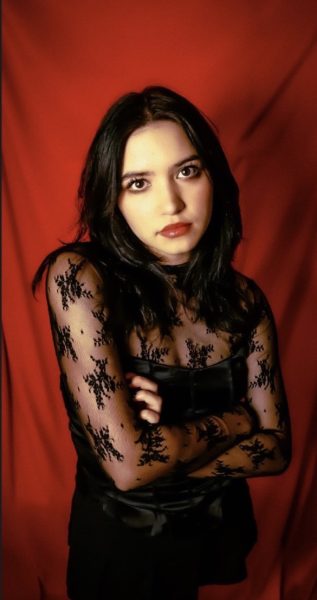

Based on the true story of con man David Hampton, who, in the 1980s, managed to convince several people that he was the son of famed actor Sidney Poitier, “Six Degrees of Separation” is the story of a young man named Paul who develops a friendship with Manhattan elite, Ouisa Kittredge, under false pretenses. Played by senior Tre Cotten, Paul enters the Kittredges’ world limping with a stab wound.

Out of context for the set, in which two-story-high deep crimson panels hold art that looks to have been bought from The Louvre, Paul stumbles into the Kittredge home, where a double-sided Kandinsky, which today is worth well over $15 million, sits prominently center stage behind the living room sofas.

With shock that tries to mask irritation, the Kittredges bring Paul into their home, fluttering between Paul, who is bleeding through his shirt but refuses a doctor, and a wealthy patron, who the Kittredges can’t help but think “$2 million” when trying to sell a painting that would keep them from “almost losing it all.”

Junior Kelly Mis added jolts of humor playing the bemused Mrs. Kittredge, who wrestles with the disheartening aftermath of being conned by Paul and charmed by his sometimes flirtatious affection, sliding in inappropriate remarks about liking Ouisa’s eyes on him, scanning his body as he moves about the room. Mis’s every move and line transitioned seamlessly into the next with a professional grace uncharacterized by most student productions, making her monologues seem more like personal conversations with the audience members. With infatuation that borders on mimicking a young girl in love, Mis bonded with the audience showing her inner conflict with Paul by reeling them in through direct eye contact, making them seem more like a friend than an observer.

Art dealer Flan Kittredge, played by Jacob Jackson, is hoping to sell an expensive painting by French Post-Impressionist artist, Paul Cezanne, to a South African gold mine owner when Paul stumbles in, putting the Kittredges’ lives into a tailspin. Jackson played the uppity air of an art dealer about to go belly-up in debt well with the “libel” talk he refused to spill whenever his wife was narrating present-day recollections of Paul. The outrage of finding Paul in bed with a male hooker was executed with hilarious dismay as Jackson’s voice reached a pitch cats would screech at. As he stumbled around the house making sure his treasured possessions, trinkets whose true value would only be known by a Manhattan elite, were safe and sound, Jackson counteracted Mis’s so far serious tone with refreshing comic relief

While Paul was not played with the smooth confidence characteristic of the original Broadway play’s leading man, Cotten does do an excellent job of making the Kittredges, and the audience, like him. Cotton was able to make the character believable and innocent, especially when he went on a tirade about the phonies in J.D. Salinger’s iconic novel “The Catcher in the Rye.” He made the con-man Paul really was into the “anti- Holden,” representing himself as an honest man with no ulterior motives. Paul then swindles another family similar to the Kittredges, a divorced Jewish doctor and, in a surprising twist, a young couple new to New York who wait tables just to make ends meet.

When the Manhattan elites realize they have been tricked by this young man, who to their giddy delight said his father would cast them as extras in the movie production of “Cats,” they try to have him arrested. Since nothing has been stolen and no crime had been committed, the complaint is received without further action.

After their first meeting, Paul is absent from their lives until an article is published about the con story. The article gives the account of how a young man killed himself after having sex with Paul and giving him all his money. It isn’t until then that Paul feels remorse and, with the defeated look of someone caught in the act, calls Ouisa to help him get out of the situation. When Ouisa pushes him to turn himself in, promising that she will help him get on his feet after it was all over, Paul relents and consents to meet her and the police.

As Ouisa, Mis was able to transform a snooty, Fifth Avenue socialite, who could only think “$2 million” when a young man was bleeding through his shirt, into a woman who, by the play’s end, softly cried into the phone, begging Paul to turn himself into the police. When Mis exited the stage the audience fell silent, reflecting on what she called “an experience” with Paul