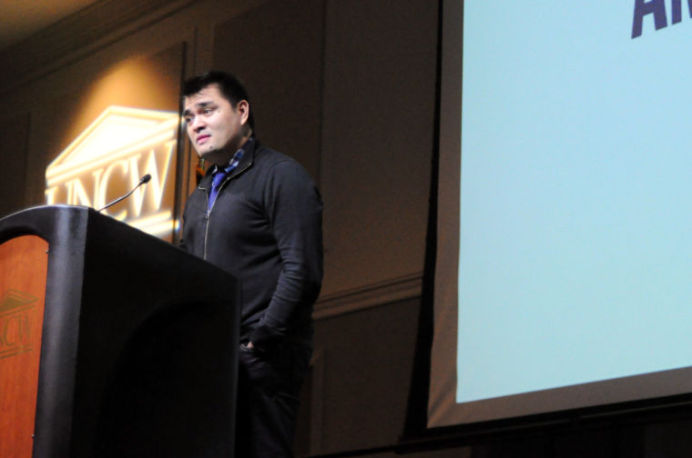

Jose Vargas speaks about his journey to be recognized

Jose Vargas talks to the UNCW community about his journey as an undocumented immigrant in the United States.

On a summer day, he rode his bike to the local Department of Motor Vehicles to get his driver’s license. He waited in line with his green card, that read “United States of America Permanent Resident” on the front, in his hand. When his number was called, he gave his plastic card to the clerk, waiting to receive his driver’s license and leave. He would not get that chance, at least not that day.

“This is fake,” the clerk said. “Don’t come back here again.”

Sixteen is the age held in reverence for adolescents everywhere—the age we can receive our driver’s license, in most states. But for Jose Vargas, a California-raised Filipino and Pulitzer Prize Award-winning journalist, it was a moment that would change his view on this country and how he existed in America.

“The agent at the DMV just knew it was a fake, and I didn’t really know what [a passport] meant legally,” Vargas said. “Whenever I heard anything about fake documents I always thought it was Mexicans. I’m Filipino and that’s not the first thing you normally think of when you think of an illegal immigrant.”

Vargas now takes time to travel to different destinations to enhance the immigration conversation and help challenge what defines America. On Monday Feb. 24, Vargas spoke at UNC Wilmington’s Burney Center.

Vargas made the trip to the United States when he was 12 years old with his uncle, a man whom he had never seen before, at the Philippines’ Ninoy Aquino International Airport. Among the few things his mother said was, “It might be cold up there,” and sent him to live with his grandparents, Lolo and Lola, in Mountain View, Calif., a mid-sized agricultural town in the San Francisco Bay area.

He thrived on the new language, culture and slang terms of the “land of the free and the home of the brave,” and he even came out as being homosexual to a high school classroom full of his peers. Despite his parents not joining him on this adventure, he felt at home. That is, until he learned he was not considered an American citizen, and his “uncle” was not actually his uncle. The anonymous uncle was a coyote, a smuggler who facilitates the migration of undocumented immigrants across the United States border.

“It was all Disneyland and Michael Jackson to me,” Vargas said. “I guess I didn’t understand I’d come here, basically be hiding here, and I would not see my mother for 20 years.”

Lolo and Lola were both naturalized citizens of the United States, so Vargas had no reason to believe that all of the paperwork and documentation given to him by his grandparents were forged. But when Lolo was forced to tell him the truth, Vargas realized that legally he was a criminal and could face deportation if caught.

Lolo paid the coyote $4,500 to smuggle in his grandson with a fake passport under a fake name. Vargas received a fake passport with his real name, a fake green card and fake student visa when he arrived to California. He had to make a decision—would he leave the country to move back to the Philippines with his mother or stay in the U.S.?

From that moment on, Vargas would not be able to live without the fear of being ousted for what he was considered: illegal. There would be very few close friends, so no one would ask questions. If he wanted to have a career, he would commit illegal acts and he’d have to rely on a limited group of people, risking prosecution, to create a decent life for himself.

Vargas made the best of a bad situation and continued with his high school education. Learning the difference between English and American “slang” was always problematic. But his high school English teacher introduced him to journalism, and after writing for the student newspaper, he was convinced that was his calling. For him, it was validation.

“I’m 17 and I thought, if I can’t be here because I don’t have the right papers to be here, what if my name was on the paper? I thought my name on the piece of paper was a validation,” Vargas said. “Now, I am all over Google. I have documented so much of America because of my job.”

But in order to even get a job at McDonalds, there is one thing everyone needs: a social security card. With the fake passport in hand, Vargas and his Lolo went to the local Social Security Administration office to receive a social security card. They took the original copy, taped over the authorization and photocopied it. His only legal documentation was now unlawful.

”One of the things I realized is our government agencies aren’t really talking to each other. The IRS doesn’t care if I am here legally, they care about whether or not I pay taxes,” Vargas said.

Vargas was a talented writer among his high school peers. He became co-editor of the student newspaper and interned at the Mountain View Voice, his local newspaper. But, that didn’t mean he would have the opportunity to go to college. Due to his immigration status he could not receive federal loans. Luckily, among those in his circle that knew of his immigration status were the superintendent of his school district and the school principal. They steered him towards scholarships that did not check immigration statuses, and he received a scholarship that paid for his education at San Francisco State University.

He already knew his career path freshman year—journalism—so he embarked on several internships and jobs. He began to work at the San Francisco Chronicle, and then interned at the Philadelphia Daily Times. The following summer he was offered another internship at the Seattle Times.

But yet again, immigration issues became a problem. A birth certificate, passport and social security card were required to partake in the internship. Fearing his documents wouldn’t suffice, Vargas confessed to the program director of his immigration status. He was later notified he could not participate.

The fear continued: if that was just an internship, how would he ever get a job as a journalist? After inquiring with Jim Venture, the capitalist who paid the funds for his education, about hiring a lawyer to fix his immigration problem, he began to feel confident. However, the lawyer told Vargas some somber news: his only resolution would be to take a 10-year ban from the U.S. and by returning to the Philippines.

Vargas decided to keep his immigration a status a secret from everyone from that moment on. No one would discourage him from his dreams based on a piece of paper. He applied to internships at the Chicago Tribune, the Boston Globe and the Washington Post. When the Post came calling, he wasn’t letting the opportunity pass by. There was only one problem—a driver’s license.

Among the easiest states to receive a driver’s license from was Oregon, and Vargas’ support network helped him. His friend allowed Vargas to use his father’s address as his own, while his high school principal and superintendent sent letters to the house under his name to prove residency. It worked. At the age of 22, Vargas was writing for one of the nation’s top newspapers, the Washington Post and paying taxes, because checking a box on employment papers makes all citizens—legal or not—pay taxes.

After interning at the Post, Vargas would return back to San Francisco to complete his degree. After college, Vargas was unsure where he would be, but the Washington Post came calling again, and they offered a two-year paid internship. He jumped at the opportunity.

In the years that followed, he was promoted to staff writer and covered issues such as video games, Washington’s H.I.V./AIDS epidemic and the role of technology and social media in the 2008 presidential race. When he visited the Secret Service, he gave them the fake social security card. It passed their inspection. In 2008, he and his writing team won a Pulitzer Prize for their coverage of the Virginia Tech shootings. For any writer looking at Vargas’ resume, he had achieved the American dream. But as an illegal immigrant, he wasn’t even close.

Regardless of the accolades, nothing changed the constant fear of being found out. In his New York Times article, Vargas said, “It was an odd sort of dance: I was trying to stand out in a highly competitive newsroom, yet I was terrified that if I stood out too much, I’d invite unwanted scrutiny.” There was no getting around it. Vargas was still hiding.

After attempting to come forward with his immigration status, Vargas would leave the Washington Post, move to New York, and begin writing for the Huffington Post. Again, Vargas wrote on a series of topics, profiling Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook for the New Yorker, and having his H.I.V./AIDS series made into a documentary. But after less than a year, he still felt too fearful and left the Huffington Post.

It was not until 2011, at age 30, that he wrote, “My Life as an Undocumented Immigrant,” for the New York Times, publicly announcing his immigration status for anyone to read.

In order to become a naturalized U.S. citizen, you must either obtain a green card, marry a citizen, or join the military. Most people don’t realize the difficulty of obtaining a green card. If not joining the military or marrying into the country, the foreign person must pass an interview, English/civics test, and be favorable to the interviewer. He or she must have certification and skills for a job that the interviewer deems worthy of a green card.

“Most Americans don’t really know what being an undocumented person in America means,” Vargas said. “We throw words like why don’t you just make yourself legal. A lot of it is just ignorance, because people don’t know. Once you humanize the issue and not make it about Republican or Democrat, the issue is different.”

Obama has deported 1.4 million illegal immigrants since the beginning of his administration, according to a Washington Post article. That means that almost 1000 immigrants are deported daily, since he has been in office. Vargas claims that $11.2 billion of tax money came from illegal immigrants last year.

“I believe we have a total disconnect with the politics of immigration laws and the effect it has on the lives of the immigrants,” Vargas said.

Since leaving the Huffington Post, Vargas has become involved in efforts of immigration reform in America. Currently, he is working with defineamerican.com, a website dedicated to talking about immigration and its broken system. He continues to state if the immigration system were willing to work with immigrants in an easier manner, this would not be the problem it is today.

“As far as I’m concerned, politics is culture unless we can change what people think of immigration and people like me,” Vargas said.

But think about the accomplishments he has been able to make despite all the obstacles he has faced. He has written for the country’s top newspapers and magazines, interviewed public figures such as Hilary Clinton, and has won a Pulitzer Prize. How many documented American citizens do you know that have done that lately?