Tales from Abroad: savoring the beauty of everyday life in France

How one UNCW student became research published as an undergraduate and spent her fall semester on a French organic farm

Emma Cowen wakes before the sun on a cool fall morning. She laces up her boots and puts on her work clothes. While the sun creeps into the sky, she walks out into a dew-laden pasture. Cowen is walking across the pasture to the sheep there. It is her job to take care of them, to brush the dirt or bugs from their fleece, to count each fuzzy head.

At 22, UNCW Emma Cowen has already accomplished what some academics only dream of. She has spent a month researching an unknown French resistance group in Lyon, France, and she spent the subsequent three months at an organic French farm doing manual labor. During that time, she wove her research from Lyon together into an article that would later be published in the peer-reviewed journal, Convergences—a feat, rare amongst undergraduate students.

Cowen’s path began with a $4,000 grant for Holocaust studies called the Alfred and Anita Schnog Travel Award. Cowen had switched her major from International Business to International Studies and wanted to immerse herself in the richness of the real world and the French language.

“I couldn’t afford to study abroad,” Cowen said, “and the programs available at the time weren’t feasible. But, as I was starting to really enjoy and appreciate the process of learning a new language, I knew that I needed to do something to fully immerse myself in order to feel more confident when speaking French.”

The idea to research a Holocaust story came to Cowen from French department faculty member Dr. Barthe, who lived in France before becoming a professor at UNCW.

After conferring with Dr. Barthe, Cowen landed on the Schnog travel award and Dr. Barthe suggested the idea to study the “Justes”—an independent and relatively unknown resistance group that saved Jewish families and children in Nazi-occupied France during World War II.

“And so, I did a little bit more research,” said Cowen, “and I was like, ‘Oh, my God, these are the coolest people…like how did they do this?’ But there was very little information on them at time, and I just started looking to brainstorm. It was like a never-ending brainstorming session that ended up taking me to France.”

The Justes, after Cowen began researching them, would be the impetus behind her unique study abroad experience and her publication in an academic journal.

After Cowen received the $4000 from the Schnog grant, she organized a Directed Independent Study, with Dr. Barthe from the French department and Dr. Andreescu from the International Studies department as her respective advisors. Her research would count as an official study abroad program, and thanks to connections of Dr. Barthe, a farm just outside of Toulouse agreed to host Cowen for the fall semester.

Cowen worked three other jobs alongside her full semester to afford a trip to Lyon, France.

“I bought a flight ticket,” Cowen said, “found an Airbnb that would let me stay there for the 30 days I needed to be there and then just explored.”

In Lyon, Cowen would spend a month sifting through French archives and primary sources for her research paper on the Justes.

Unlike members of the French Resistance, who were honored for their bravery with medals and memorials, the Justes remained anonymous and eventually faded into the folds of history. The Justes used a series of secret passageways, known as “traboules,” to work under the Nazi’s noses. They operated in Lyon during the Vichy regime and utilized this network—which wind their way through the city in courtyards, hillsides, buildings and staircases—known only to true longtime residents of Lyon.

For this reason, there is relatively little research published about the Justes—making Cowen’s all the more significant.

“These people didn’t even want to be known for being in their existence,” said Cowen. “So, whether it be out of fear, just because they were humble, and felt like they were doing their civic duty, or that it was morally right at the time.”

In Lyon, Cowen met an 80-year-old French man named Micha who would drive her throughout the city and give her accounts of the history tucked within its walls. Cowen’s research culminated in a 27-page paper which she submitted to the journal Convergences—an affiliate of the Southeastern Association of Cultural Studies (SEACS).

“As I had people reviewing my drafts prior to submitting, they kept telling me that the research was strong,” Cowen said, “but not to get my hopes up because getting published can be a challenge, and if you do get accepted, the process is quite demanding. So, I was shocked, to say the least, when I received my feedback and acceptance for publication with only one slight revision.”

Cowen was one of few undergraduates to attend the corresponding conference at SEACS and was one of the only undergraduates who would eventually be published.

After a month in Lyon, Cowen traveled to London to stay with her aunt before journeying back to France to stay on the organic French farm near Toulouse where she lived for three months.

The farm specialized in wheat production, and using their own mill, they transformed fields of grain into flour. The farmers, Blandine and Daniel, kept cows and sheep.

On an average day, Cowen woke at six o’clock—despite not being a morning person beforehand—and fed the animals, led them into pasture, and then returned to the farmhouse for breakfast. “Mealtimes were very important,” said Cowen. After breakfast, she finished a project or another chore around the farm before their two-hour lunch and coffee midday break.

“When they were first getting to know me and whatnot,” Cowen said, “I started out with basic tasks like just following Blandine to market and selling the flour with her, and I would give the food every day to the cows, to the baby cows who lived in the barn and to the sheep.”

Cowen’s French during those first few weeks was still burgeoning, as she’d spent most of her time in Lyon reading and writing in French as opposed to conversing daily. Now, staying with her hosts Blandine and Daniel, Cowen honed her speaking skills and learned to adapt to a rural French lifestyle.

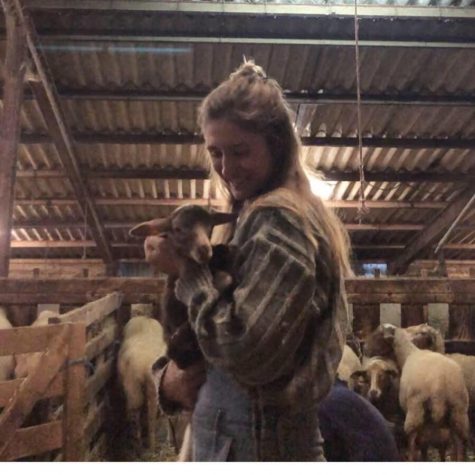

“And then I learned to shepherd and was shepherding 260 plus sheep,” Cowen said. By October, lambing season had begun. “So, I would bring these sheep in every night, but sometimes they would have babies out in the field and the field was like, a mile away. So, I would be walking back with two baby lambs under my arms.”

Besides learning how to care for animals and shepherd a flock of sheep, Cowen learned how to drive a tractor, forage for mushrooms or edible plants, make bread from scratch, chop wood and to simmer green tomato jam.

One of the most important skills Cowen learned wasn’t about work or striving for success: it was learning how to savor the mundanity and beauty of everyday life.

“The popular saying is, Americans live to work and the French work to live,” Cowen said. “And I think that redefining how we live and understanding what it means to be living is very important.”

After her time abroad, Cowen turned her attention to researching stories about people humbly making a difference in their communities. “I want to give people the credit they deserve and hope that by me writing about it. people will read it and understand that good things are still happening. It’s not all bad all the time.”

Kathleen Borner...yaya • Feb 14, 2021 at 9:23 pm

Very proud of you Emma Rose Cowen….

Dick Borner • Feb 11, 2021 at 9:07 pm

I applaud Seahawk’s feature of Emma Cowen not only on how well the article was written, but in the selection of Ms. Cowen and in describing what she has accomplished as an undergraduate student at UNCW. As a long time fan of Emma, perhaps a bit biased as her uncle, I was thrilled that you described the incredibly scholarly and moving research she did looking into the secret work of the Justes saving thousands of lives of refugees in Nazi occupied France during World War II. You then described Emma’s subsequent work on the farm in France with such detail as to make the reader truly understand her experience. Thank you. DB

Sent from my iPad

Jo Gallagher • Feb 11, 2021 at 8:12 pm

What an adventure Emma Cohen went on. Getting research published is not small feat, especially while still a student. What I liked most was the stories from the farm. It sounds like bucolic splendor!