The term ‘African American’ does not sit well with me

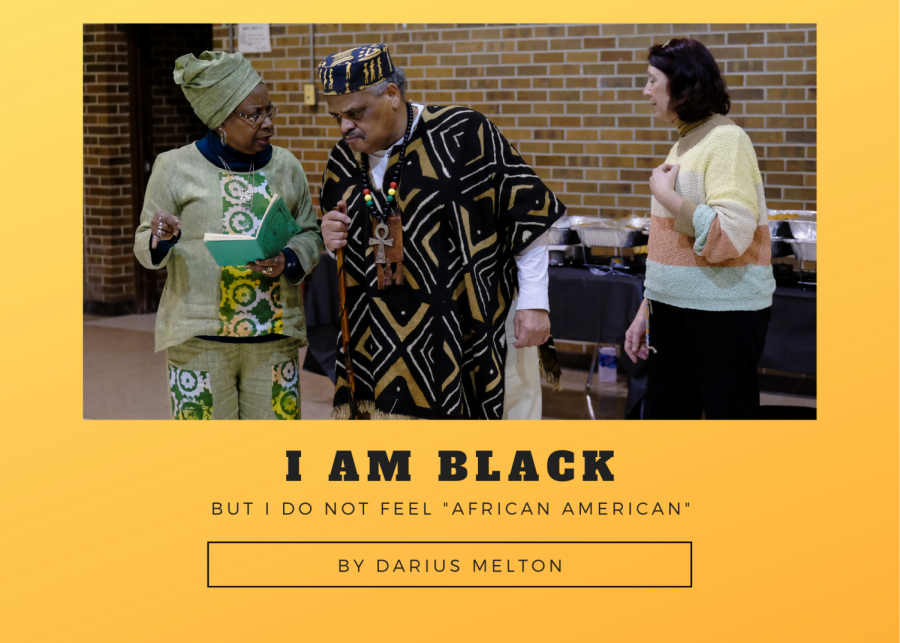

Riley Yuan

Attendees chat and mingle at SACF’s Kwanzaa event on Dec. 31, 2019 at First Ward Community Center in Saginaw.

EDITOR’S NOTE: For the purposes of putting the term “Black” on a pedestal equal to that of “African American,” I have chosen to capitalize the term in this article. This is not proper AP style—we do not capitalize the “w” in “white,” so “black” typically follows the same conventions—but for both myself and the interviewee, we have chosen to forego AP style just this once.

The debate over the “right term” to refer to groups by has changed a lot in the past decade. Outdated names like “midget” and “retard” are being traded out in favor of “little person” and “mentally handicapped,” and there has recently been pushback against the flagrant usage of words like “crazy” because it belittles legitimate issues that are more than just “craze.”

To some, all of these discussions boil down to simple semantics. However, taking into account the effect of threats, slurs, gaslighting and any other number of ways to verbally abuse people, it is clear that words mean something.

Before I continue, I do want to stress that I do not speak for all Black Americans—and no one “speaks” for all of their race, for that matter. All anyone can do is speak to their own experience. That being said, in my experience, I am not comfortable being labeled as an “African American.”

It is not an offensive term—it is simply inaccurate and not indicative of my family’s story.

Valerie Keys, a senior majoring in communication studies and minoring in political science—who also happens to be the managing editor here at The Seahawk—shares this viewpoint, attributing her take on the debate to being surrounded by genuine African Americans in her hometown of Fayetteville. With Fayetteville being home to a historically black college/university, many African students and professors were around and able to talk to her about their experiences.

“That was the first introduction I had to African culture and how detached I was from it. And it’s not like it’s a bad thing, but these are people who are from Nigeria, Ghana, Egypt, and they came here and became citizens. They’re doing their thing and they’re living life, and they’re enjoying it, and they say that they’re African. To me, that’s African American, because you have a direct line to the culture,” Keys said.

When my classmate tells me he has Chinese ancestry, he can point to the grandparents he visited in China. When my best friend tells me that she is Mexican American, she can tell stories about living in Mexico as a small child. When a mutual friend of mine celebrates his Scottish heritage, he does so by visiting a castle in Scotland that falls under his family name.

My last name is Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian. I am not. But I am not really African, either.

I am 100 percent positive that, at some point, my ancestors were in Africa, and not too long after, my ancestors were transported to America. At that point, though, they were not truly Americans. They were Africans, enslaved and not even given the opportunity to adjust in this new land, at least not in the way that “real” Americans were.

This kinship that came from being Africans removed from home is what carried these enslaved Black folks through trying times, but this in of itself was a new culture. They were not just removed from home, but removed from their culture, and in the wake of leaving Africa behind, a new Black American culture was formed.

Black-led churches, soulful music, Black cuisine like chitterlings. This was Black culture, but it was not African culture, and the differences only grew from here.

Though its roots are across the ocean, rap music is not African culture. Neither is the movie “Friday.” You may hear a Beyoncé or Stevie Wonder song while listening to the radio in Africa, but they are not icons for African culture like they are for “African Americans.”

There is a divide—and thus a cognitive dissonance in my mind—between the African, the African American, and the Black American.

Taking a 23 and Me test can tell me where in Africa the majority of my genetics come from, but it will not be a clear-cut answer. I come from two long lines of Black, and my parents come from their own lines (that makes four more), and their parents have their own (that makes eight). We are made up of so much assorted Black that I cannot find it in myself to claim any culture other than the American melting pot that everyone I just mentioned was born in.

Keys, too, feels a disconnect from the term.

“I don’t feel like it’s me disclaiming my African heritage, but I don’t know that heritage. I don’t know that part. I haven’t done the history and the homework to really find that out and connect with my roots. I’m not saying I’ll never do that—I could one day, but I haven’t taken the time to do that yet—but in terms of Black American culture, that is me to a tee. That is the way I grew up. That is the way I experience life on a daily basis, from hip-hop to playing spades to having the uncle who wears the Jesus sandals who is always at the cookout,” Keys said.

Of course, there are many people who prefer African American to Black; in fact, it is a name we gave ourselves after Rev. Jesse Jackson coined it in 1988. There are also people within the Black community who feel there are much bigger things to worry about than inoffensive names—and maybe they are right.

But when a Black American travels to Africa, or an African emigrates to America, the ties between us tend to only be skin-deep. For this reason, being called African American does not sit well with me. I am too far removed from Africa to claim it as my home, and while I can admire that land’s place in my history, it is not my land.

I am an American, and I am an American who is Black. It is as simple as that.