Sand, in sanity

Kyle McAfee’s wildest day in Afghanistan wasn’t the day he arrived at Camp Leatherneck, or even the day he got his first kill; it started out as just another clear, hot day on patrol in Helmand Province, Afghanistan.

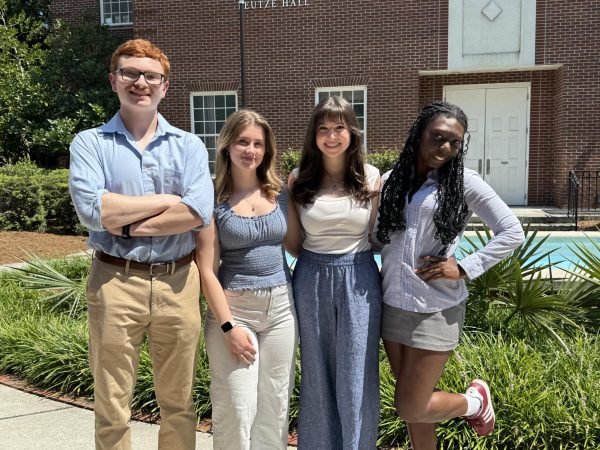

McAfee is Marine, lance corporal, mortarman, with his wife on one hip and a gun on the other outside a Wilmington, N.C. residence as he tells his story, a Coors Light in hand.

He remembers his scalp, kept high and tight, was sweating beneath his helmet that day, but he was thankful for his helmet; it stopped the sweat from sliding into his eyes, burning them. Equipped with the standard-brown, sweat-stained Flak jacket, rounds of ammunition and weapons on his hips and in his pack, he was joined by the 3rd Marines, 2nd Battalion*. The team was over a mile from the forward operating base, or FOB, when they began to catch fire from a group of insurgents.

Preparing to engage the enemy, McAfee had the shooters in his sights. His weapon was aimed in their direction when suddenly, the bullets stopped coming. Instead of running for cover, the shooters were running towards them.

Easy, McAfee thought. Too easy.

Glancing up from his gun, McAfee saw a wide, ominous brown cloud expanding over the horizon; almost like the dust cloud of dry season, and not quite as localized as the mushroom cloud of an atomic bomb, but with the consistency of smoke rising from the center of a canyon.

McAfee knew what it was. He thought quickly. No time to drop gear. No time to call for a ride back to base. They’d be lucky if they had time to run to shelter. Ten minutes, tops.

He picked up his weapon and gear and started to run too. The rest of his team was instantly on their feet and on McAfee’s heels.

A sandstorm was coming.

A dance with danger: duty in the desert

Unpredictable, violent and prevalent in arid zones like Afghanistan, sandstorms epitomize the war in the Middle East. They are caused by massive winds that vibrate loose sand particles, which saltate, or leap from the ground. When the particles bounce, they break off more particles, and the sand travels in suspension; sometimes for days, sometimes for weeks.

They have been known to trap soldiers on patrol for hours with only a blanket and goggles for shelter.

Sandstorms can take the form of twister-like columns that dance across the desert to a thunderous bass and the crescendo of lightning. The rain, hot like sweat, falls sideways as the wind slices the harsh landscape like a thousand whips striking the sand. When the Marines see one coming, they know they have about 10 minutes to stack green, rectangular 30 to 80 pound ammo cans around any gear left at post and hustle to the nearest tent, or buckle down and ready themselves for a bumpy ride.

Outside the tent, winds would be strong enough to knock the Marines over. Inside, their combined weight forced the tent down, keeping thrashing wind from picking them up and trash their gear.

Like a Nor’easter from hell

Sandstorms can sit over the desert for weeks and leave sandbanks, like snow banks, piled up against the mud huts in which most Afghan people reside. Irrigation canals that fill with sand can devastate farmers; scourging winds displace the soil in dry land farming and can ruin a crop. If not covered, wells can fill up too, denying villagers of clean water for weeks. Sometimes villages require evacuation.

“When it stormed, the tent almost blew away every single time,” says McAfee. “We’d look for any patterns in the dirt, disturbed earth, stick formations; not rock formations because civilians use those to find their way to bazaars.”

But sandstorms severely reduced visibility, which increased the risk of injury or death and often affected land and air operations. There were no plow trucks to remove the sand; instead, the Marines would roll over the mountains of sand, paving a new dirt road with their tire tracks.

McAfee’s team was on a patrol about a mile and a half from base when they felt chunks of hail bounce off their helmets.

“We had sandstorms where you could identify your hand but you couldn’t see it clearly,” McAfee continues, “But in this sandstorm, you couldn’t see anything.”

Away from their post, there was nothing to protect their gear if they left it behind; McAfee and the other Marines ran to an Afghan police station for safety, laden with up to 80 pounds on their backs. He laughs at the irony of hail in the desert; like bullets raining from the sky, and just as dangerous.

“You hear about hail killing people, but it didn’t matter because of the Kevlar,” he says.

His team waited out the worst, and then cautiously made their way back to their tents; any markings for IEDs they had made on their way would have been swept away by the storm, so each footstep could be their last.

Inside the tents, the Marines would grow restless, like children cooped up inside on a rainy day. Some were thankful for the downtime, and would write letters home or watch movies, play PS3s or read. They would joke about taking their parachutes and riding the storm, like a game of windsurfing in the desert. They would catch up on sleep during storms, huddled beneath thin blankets on cots pushed towards the center of the tents, waking sporadically to the howls of Afghan wind.

American Spirits

Terrible weather didn’t always stop the Marines from having fun. Lance Corporal Richard Staats, with 3/2 remembers when his commanding officer offered a whole carton of cigarettes to anyone willing to run naked across the base.

Staats didn’t get a lot of care packages. A whole carton might last him a week, maybe two if he stretched it. Many Marines had used the deployment to help themselves quit; the shaky hands and food cravings, common side-affects of detoxing from the additive nicotine present in most cigarettes, can make pulling a trigger pretty tricky.

But Staats liked American Spirits. He liked them because they stood out to him on smoke shop shelves, but more for their stress relief than for their brightly colored boxes with the Native American head on the side.

His favorite brand was different from the other Marines, but the desire was the same. Without hesitation, the Marines shed their gear. They shook off their heavy boots and stripped off their socks, bolted from their cammies and flew from the tent’s flaps wearing nothing but smiles, tattoos and dog tags.

Into the sandstorm they went, their chiseled naked forms disappearing into the brown haze.

“We were kicking up dust and sand,” Staats remembers, “It was pouring.”

Staats got back to the tent first with a victor’s grin plastered across his face. He was shivering; his red skin was soaked and peppered with grains of sand embedded on his legs, arms and torso.

His commanding officer handed him his prize. It wasn’t the bright yellow box with the Native American head on the side. He wanted the bright yellow box. He craved the bright yellow box. The bright yellow box meant American Spirits cigarettes.

Spirits would get him through the sandstorm without suffering from severe boredom. Spirits would give him the patience to make it through the day in the airless, crowded tent. Spirits would help him ignore the sand in his boots, the sand in his food, the sand in his sheets, the sand in his water. Spirits would give him the energy to wipe the sand from his eyes and the corner of his mouth, and the calm that sleep would require to suppress the storm in his soul, while the gale winds of an Afghan sandstorm raged a few feet from his head.

They weren’t American Spirits, that much was clear. But they would do.

*The following correction was submitted July 3, 2012: McAfee was with the 2nd Marines, 3rd Battalion, the same battalion to which the four Marines in the Youtube video belonged to.