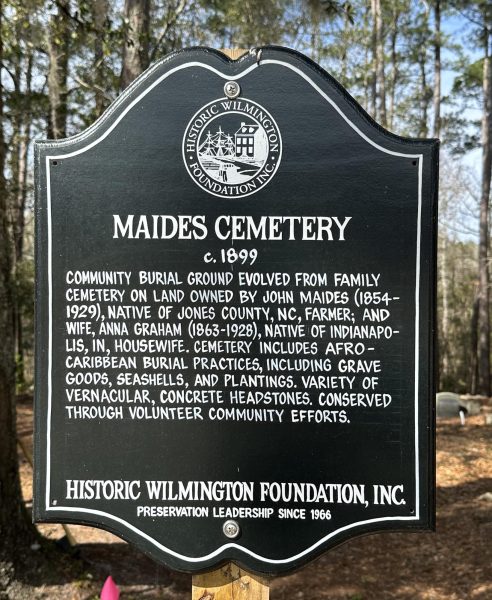

On Feb.10, local volunteers gathered at Maides Cemetery with a Ground Penetrating Radar System (GPR) to help uncover gravesites for individuals buried at the cemetery. For some, this means finding gravesites for family members. This project is a collaboration between the Historic Wilmington Foundation and the Public History program at UNCW with Kathy King, a descendant of the Maides family and participant in the search.

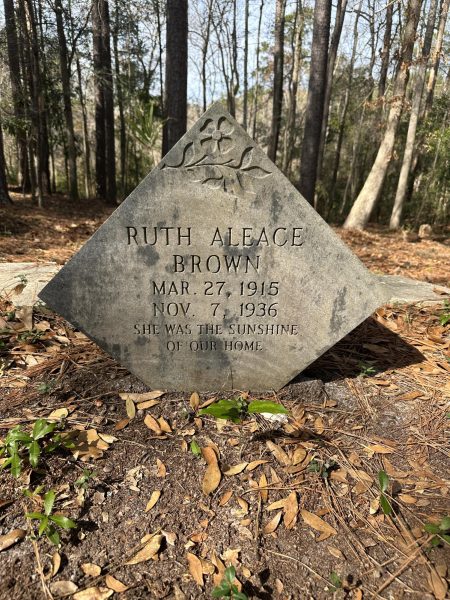

Maides Cemetery is a historic African American cemetery that has graves dating back to 1899. It started as a family cemetery for the Maides family, and later included families from the surrounding community. King, confirmed that there are 216 burials listed at Maides Cemetery, but there are only 81 marked graves.

King hopes to find the gravesite of her sister, Carolyn King, who died in 1966. “I know she is buried here, I just do not know where she is buried,” King said. “There are Maides family members that I think she is buried in the vicinity of because I have discovered that I am a descendant of the Maides family.”

The last known burial at Maides Cemetery was King’s sister in 1966. She died at 19 after drowning on Topsail Island. King’s family did not have the chance to give her a proper burial.

“I want to put a headstone on it [her sister’s grave],” King said. “My mother and father never had the opportunity to, they could not afford it. That is what I hope to do when I find her grave.”

The cemetery was unattended until May 2021 when volunteers and relatives of those buried at the cemetery worked to restore it. Isabelle Shepherd, the development officer for the Historic Wilmington Foundation, began the restoration with King.

“At that time this cemetery was unrecognizable,” recalls Shepherd. “The brush had grown absolutely wild. There was a buildup of leaves, and it took months for the cemetery to reach a point where it became maintenance instead of repair.”

Today, Dr. Scott Nooner, a geology and geophysics professor at UNCW, is using GPR to locate the unmarked graves.

“This is a noninvasive technique that uses pulsive radar energy which is a type of electromagnetic energy,” said Nooner. “That energy travels into the subsurface and some of the energy is reflected off any changes in the subsurface. This is a technique that is commonly used in archeological and cemetery surfaces to try to identify potential grave sites without having to dig things up.”

Nooner is using the GPR to look for disruptions in the ground’s natural sediment layers. It then compiles the data into one large data site where Dr. Le Zotte, the director of the Public History MA program, and her grad students try to identify the people. However, Le Zotte confirms that it is impossible to be completely accurate without digging up the graves and using invasive techniques.

“A lot of the earliest graves in 1899 were children sadly, because of high infant mortality rates among Black populations was a fact of life at the turn of the century,” says Le Zotte.

This collaboration between the Historic Wilmington Foundation and UNCW’s Public History program is years in the making, and today is the first time GPR is used at Maides Cemetery.

“My sister was 19. She had just graduated from high school and was getting ready to go off to the University of Wisconsin in Madison,” says King. “It means a whole lot to be able to try to find her grave and also give honor to the other people who are buried at this cemetery.”