On Oct. 30, beachgoers of Emerald Isle discovered a Gervais’ beaked whale in the shallow water. The Emerald Isle Police Department and Emerald Isle Public Works removed the whale from the water and ensured its transportation to NCSU. Shortly after, Dr. Vicky Thayer (North Carolina State Stranding Coordinator) and her team responded and confirmed the whale’s death. A necropsy, an autopsy for animals, was performed by scientists, students, and veterinarians from the NCSU Center for Marine Sciences and Technology, the NCSU College of Veterinary Medicine, UNC’s Institute of Marine Science, the Duke University Marine Laboratory, the NC Division of Marine Fisheries, the NC Maritime Museum Bonehenge Whale Center and UNCW’s very own Marine Mammal Stranding Program. The confirmed cause of death was a Mylar balloon lodged in one of the animal’s three stomachs. The whale was identified as a young female calf because it had milk in her stomach in addition to the balloon.

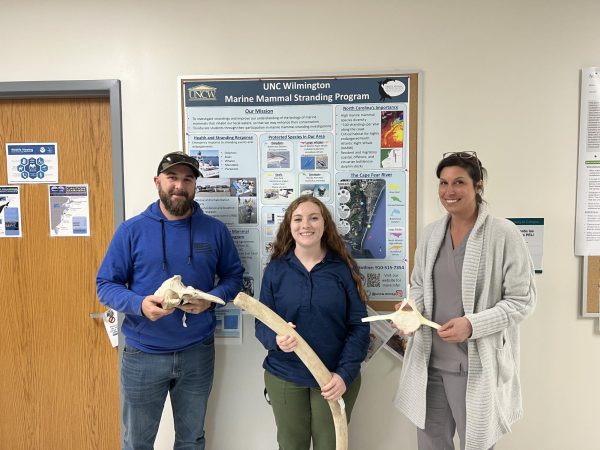

The balloon was a pentagon shape, about 28 centimeters by 36 centimeters, and appeared to be deflated. Dr. Tiffany Keenan, a post-doctoral fellow and the Stranding Coordinator for the Marine Mammal Stranding Program, spoke on the likelihood of an occurrence like this.

“They are rather infrequent; we get about two a year throughout the entire state,” Keenan said. “They are very, very rare. We would see them on aerial surveys more often.”

Keenan and Alison Loftis, the Assistant Stranding Coordinator for the Marine Mammal Stranding Program and a UNCW Alumni of 2021, stated Gervais’ beaked whales are found anywhere from 100–300 miles off the coast and continental shelf. Cape Hatteras, 174 miles north of Wrightsville Beach, serves as a hotspot and contains the largest population of Gervais’ beaked whales in the world; but, according to Keenan and Loftis, most people do not know about their existence.

“People don’t even know about [beaked whales], but somehow, our trash reaches them,” Keenan states. “That’s the crazy part.”

The beaked whale got its name from its lack of teeth and the formation of its bone structure resembling that of a beak. The beaked whale’s eating process also consists of suctioning their prey, mainly squid, through their mouths. Because of this suction power, beaked whales cannot regurgitate the food they eat. Therefore, the whale found at Emerald Isle would not have had the capability of getting the balloon out of its system.

Loftis explained why marine animals end up stranded on beaches in the first place.

“Often, in our area especially, animals strand because they have something wrong with their health – something going on internally.”

She indicates marine animals can also become “confused with their navigation,” and this is commonly due to parasites within the brain. Keenan said that in most cases they have come across, parasites in the brain are present in each necropsy.

Both Loftis and Keenan confirmed that the beaked whale most likely ingested this balloon thinking it was food. The Marine Mammal Stranding program confirmed that at least 80% of the beaked whales they respond to have some sort of plastic in their system. This is also very common with other animals – like sea turtles who may think a plastic bag is their jellyfish dinner.

Keenan stated that in her time working with marine animals, she discovered a Sei whale, the third largest whale in the world, with a CD/DVD case that had sliced its gastrointestinal tract.

“Unfortunately, because these animals do carry around blubber that is an energetic storage, it can take a long time for them to starve to death. So, it becomes an animal welfare issue,” Keenan said.

Other marine animals that the Marine Mammal Stranding Program encounters are bottlenose dolphins and humpback whales, both of which are often harmed by contact with humans.

Dr. Michael Tift is the Program Lead for the Marine Mammal Stranding Program and is also an assistant professor in both biology and marine biology at UNCW. He stated that this was his first ever encounter with a beached beaked whale, but that it is just another example of balloon pollution he has seen.

“Many times, you will see balloons in deserts. The Mojave Desert is a place I have spent quite a bit of time in out in California, and there are a lot of balloons that end up there…Even when you are out in the middle of the ocean, talking about going to Antarctica, you can see balloons in the water. It’s just an incredibly sad thing to see.”

Cape Hatteras was designated as a Monitor National Marine Sanctuary in 2017 and is home to about 27 different cetacean species (dolphins, whales, porpoises). Keenan also explains that the coast of N.C. contains a wide array of marine life due to the mixing of currents like the Gulf Stream and Labrador Current. Because of this, the Marine Mammal Stranding Program believes that UNCW has a unique perspective and ability to do its part.

Loftis further stated there are so many individuals in the Wilmington area who depend on the ocean for their livelihood, and that this is an opportunity for “Wilmington to be the leader” and “lead by example.” Loftis encourages students to start conversations with their families and bring these topics up to make everyone more aware of the changes that need to be made.

One thing Keenan stated that she would love for students to know is how many UNCW graduates are involved in communities all over the country that work to protect and care for marine animals. Furthermore, both she and Loftis began their relationship with the Marine Mammal Stranding Program by starting as volunteers. “The Seahawk is kind of all around the country,” Keenan states. “It gives great connections for students too.”

For more information: visit the Marine Mammal Science Online Library.

This article was updated Dec. 1, 2023.