REVIEW: The unsettling black comedy of “Shiva Baby”

The contained thriller isn’t a new idea in the general scope of cinema history. Many films have told the bulk of their stories within the constraint of a single time and location—comedies like “His Girl Friday,” dramas like “Malcolm & Marie” and science fiction stories like “Gravity” are all famous in part because of how the main beats of their story unfold over the course of a single day or night or even just a handful of hours.

Most often, stories with this structure happen to be adaptations of plays, such as “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” or “One Night in Miami”—of course, this may be why the black comedy and uncomfortable cringe of “Shiva Baby” is so readily reminiscent of Oscar Wilde’s “The Importance of Being Earnest.” Both stories’ jokes stem from misunderstandings caused by lies, but it’s the cinematic approaches utilized in “Shiva Baby” that set the film apart as a brazen new direction for contained thrillers and black comedies.

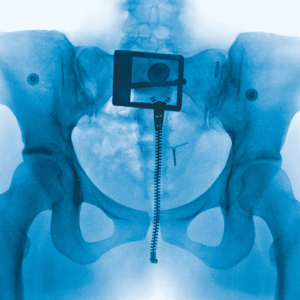

((Emma Seligman/ Neon Heart Productions))

The film centers around a bisexual Jewish college student, Danielle (Rachel Sennott), who attends a shiva with her family—shivas being gatherings that relatives of a recently deceased Jewish person all attend to mourn the loss and accept each other’s fellowship. Danielle doesn’t know or care who died, much to the chagrin of her ex-girlfriend Maya (Molly Gordon). Danielle is in for a surprise, as her secret sugar daddy Max (Danny Deferrari) is also there and the presence of his wife and baby threatens to unravel Danielle’s livelihood at its seams.

Written and directed by debut filmmaker Emma Seligman, “Shiva Baby” clocks in at 77 minutes and fails to waste a single second. The film hones in on Rachel Sennott’s vulnerable portrayal of Danielle, keeping in sync with her point of view and framing it with multiple camera techniques, including a raw close-up handheld camera and claustrophobic still-frame shots. The film dances around a well-developed ensemble of family members, both mocking their obliviousness and weaponizing it against Danielle’s security over her situation. The musical score by Ariel Marx, with its sharp, shrill violins bespeak of horror material, like the scores from “Hereditary” or “mother!”, and bleeds into the comedy to communicate to viewers just how nerve-wracking these hours at the shiva really are for Danielle.

Filmmakers and critics often point out how difficult it is to craft a film within strict temporal and special limitations. After all, the narrative of conveying high tension and drama within a very condensed location is what led “Room” director Lenny Abrahamson to an Oscar nomination for best director in 2015. But Seligman expertly utilizes the limited space of the house party where the shiva’s taking place, creating the tight effect of a net of trouble closing in on Danielle’s lie. The dialogue reveals the unwitting nature of the family members, oppressing Danielle with the threat of them finding out about her relationship with Max while also signifying their relationship with her. Most importantly, Seligma never forgets to frame Danielle in an empathetic light, even in the face of Danielle’s pervasive flaws.

In short, “Shiva Baby” is an innovative independent film that breathes new life into its subgenres—perhaps into the medium of film in and of itself. It is a delicious situational comedy that depicts its Jewish and bisexual communities in honest, complex and fascinating lights. The film is available on VOD platforms such as Google Play, AppleTV+, and Amazon Prime, and avid cinephiles would be remiss to skip it.

Gavin C • May 5, 2021 at 10:19 am

I don’t think it’s necessary to cast Jewish actors in Jewish roles(and vice-versa); it’s more important to utilise an actor who can deliver the best performance and bring the character to life.

Bee • Apr 11, 2021 at 10:27 am

It tediously casts Jewish Dianna Agron as a non-Jewish foil to the Jewish lead (played by non-Jewish Rachel Sennott).

In fact, it’s one of Sennott’s two Jewish starring roles in 2020. I hope she does Chinese next!

Casting directors should memorize this list:

Actors with two Jewish parents: Mila Kunis, Natalie Portman, Logan Lerman, Paul Rudd, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Bar Refaeli, Anton Yelchin, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Emmanuelle Chriqui, Adam Brody, Kat Dennings, Gabriel Macht, Sarah Michelle Gellar, Erin Heatherton, Lisa Kudrow, Lizzy Caplan, Gal Gadot, Debra Messing, Gregg Sulkin, Jason Isaacs, Jon Bernthal, Robert Kazinsky, Melanie Laurent, Esti Ginzburg, Shiri Appleby, Justin Bartha, Margarita Levieva, James Wolk, Elizabeth Berkley, Halston Sage, Seth Gabel, Corey Stoll, Michael Vartan, Mia Kirshner, Alden Ehrenreich, Julian Morris, Asher Angel, Debra Winger, Eric Balfour, Dan Hedaya, Emory Cohen, Corey Haim, Scott Mechlowicz, Harvey Keitel, Odeya Rush, William Shatner, Leonard Nimoy.

Aaron Taylor-Johnson is Jewish, too (though I don’t know if both of his parents are).

Actors with Jewish mothers and non-Jewish fathers: Timothée Chalamet, Jake Gyllenhaal, Dave Franco, James Franco, Scarlett Johansson, Daniel Day-Lewis, Daniel Radcliffe, Alison Brie, Kristen Stewart, Joaquin Phoenix, River Phoenix, Emmy Rossum, Ryan Potter, Rashida Jones, Jennifer Connelly, Sofia Black D’Elia, Nora Arnezeder, Goldie Hawn, Ginnifer Goodwin, Judah Lewis, Brandon Flynn, Amanda Peet, Eric Dane, Jeremy Jordan, Joel Kinnaman, Ben Barnes, Patricia Arquette, Kyra Sedgwick, Dave Annable, and Harrison Ford (whose maternal grandparents were both Jewish, despite those Hanukkah Song lyrics).

Actors with Jewish fathers and non-Jewish mothers, who themselves were either raised as Jewish and/or identify as Jewish: Ezra Miller, Gwyneth Paltrow, Zac Efron, David Corenswet, Alexa Davalos, Nat Wolff, Nicola Peltz, James Maslow, Josh Bowman, Andrew Garfield, Winona Ryder, Michael Douglas, Ben Foster, Jamie Lee Curtis, Nikki Reed, Jonathan Keltz, Paul Newman.

Oh, and Ansel Elgort’s father is Jewish, though I don’t know how Ansel was raised. Robert Downey, Jr., Sean Penn, and Ed Skrein were also born to Jewish fathers and non-Jewish mothers. Armie Hammer, Chris Pine, Emily Ratajkowski, Mark-Paul Gosselaar, and Finn Wolfhard are part Jewish.

Actors with one Jewish-born parent and one parent who converted to Judaism: Dianna Agron, Sara Paxton (whose father converted, not her mother), Alicia Silverstone, Jamie-Lynn Sigler.