OPINION: What it’s like to have autism during a pandemic

COVID-19 has been devastating.

Millions worldwide are dead from the virus, and tens of millions of people are sick. Hospitals on every corner of the globe are overwhelmed, and medical workers are exhausted. Many survivors continue to experience symptoms for months, and a few never fully recover. COVID-19 spreads silently, oftentimes transmitting among people with few or even no symptoms. In response, unprecedented orders to self-isolate from others, wear protective equipment in public and stay home as much as possible have been issued on every continent. The measures, along with general fears of falling ill or dying, have disrupted billions of livelihoods, causing a catastrophic impact to the mental health of many.

Photo by EpicTop10.com is licensed under CC BY 2.0

But that impact has been especially pronounced for me because I have a confirmed diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Symptoms can include developmental delays, restricted thoughts and behaviors, difficulty socializing, impulsiveness and even the inability to speak at all in severe cases. Even mild, high-functioning autism, like mine, poses significant challenges. My own case has entailed rigid thinking, difficulties with reading comprehension, inappropriate or “weird” social interaction and delayed milestones, on top of all of the emotional issues I have lived with over the past several years.

The condition comes with an extremely strong risk factor for various mental-health problems. A 2016 survey of 42,283 caregivers of U.S. children ages 3 to 17, some with ASD, non-ASD conditions and no conditions at all, found that 77.7% of children with autism have at least one mental health condition. Half of all autistic children, not just the 77.7%, also had two or more issues.

Unfortunately for me, I would fall into the two-or-more group. I have been formally diagnosed with depression and have also shown anxiety-like symptoms. Found in 15.7% of the surveyed guardians’ children with autism, and probable anxiety, with roughly 40% of these same children. According to the CDC, these disorders affect 3.2% and 7.1%, respectively, of all U.S. children 3 to 17. This means that children with autism are five times more likely to suffer depression and five-and-a-half times at greater risk for anxiety.

In terms of the COVID-19 pandemic, my autism has left me without a close circle or “bubble” of friends. While I do have a large number of friends, they do not really know one another and already have their own bubbles. Most students’ social lives are ring-shaped, but mine has more or less resembled a star topology. As a result, I have not been able to hug or be close to someone besides my parents for almost a year. This has had a cataclysmic impact on my mental health.

And yes, you read that right: I have not had any physical contact with any of my friends for the entirety of the pandemic.

To add insult to injury, the social isolation guidance has been wantonly vague. Aside from periodic lockdown, closure, or curfew orders, the messaging has always remained the same: wear a mask and stay six feet apart. While these two rules are arguably the most important ones to stay safe, they lack information on ways to make following them easier, including forming and managing bubbles where friends can gather without having to follow infection-control procedures. This lack of information puts the mental health of single, socially challenged people like me at serious risk.

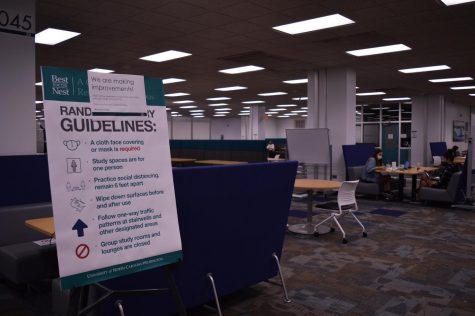

UNCW’s approach is unfortunately not any better. Their plan mimics that of the state, aside from tougher enforcement of the rules. A walk through campus reveals a very Orwellian landscape, a stark contrast to the happy, energetic community before the pandemic. Signs, arrows and rules are everywhere, even as everything looks deserted, and students on campus do not dare to talk to one another. Meanwhile, the administration abruptly changes policies and threatens severe sanctions for even minor violations. First they warned of fines and jail for those caught partying, and now students can get written up for simply eating inside the library!

Unfortunately, this type of response, referred to as “abstinence-only,” ignores students’ needs for close, physical contact and social interaction. Administrators blame and shame students, and always seem to be putting in new policies whenever cases spike. Curbing large gatherings and limiting viral spread is important, I must admit, but campuses must also strike a balance between keeping students physically healthy and mentally healthy. But, since that is not happening, students have been split into “haves” and “have nots.” While well-to-do students have been able to bubble up and preserve a semblance of normal college life, others, like me, have essentially remained locked down with their parents for an entire year.

And sadly, there is still no end in sight to my plight. Until very recently, life in the U.S. was projected to return to normal by summer or early fall 2021, with significant improvements possible as early as spring. But now, scary new mutant strains of COVID-19 are taking off, including the partially vaccine-resistant B.1.351 variant first identified in South Africa. A patient who had previously recovered from the original strain of SARS-CoV-2 tested positive for the mutant and was in critical condition, and in the U.S., multiple B.1.351 cases had already been reported. As a result, Dr. Fauci and President Biden just warned that we could remain under lockdown into 2022.

Another year of being stuck with my parents. Another year of lost college experiences. Another year of dashed hopes. Another year of unmet emotional needs. Another year of irritability. Another year of grief. Another year of boredom. Another year of, to put it simply, hell.

If more mutants emerge, and they can evade antibodies and vaccines, it could be even longer.

For those suggesting that timeline is overly pessimistic, note that one year ago today, an article I wrote speculated there was “no telling how deadly the coronavirus would become” amid projections that a vaccine was 18 months away. That particular comment felt very absurd and paranoiac at the time. But those words ended up perfectly foreshadowing an imminent pandemic, which has now killed 2.5 million people worldwide, including 500,000 Americans. Now, there is no telling how deadly COVID-19 variants could become, especially as they accumulate mutations to evade immune responses and grow exponentially.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the unprecedented response to it have been inconvenient and burdensome for everyone. The last thing anyone needed was to stay home, not meet new people and worry about disease and death for a year. But for those on the autism spectrum, myself included, the social distancing measures and closures have been devastating. They have shattered critical support systems, induced withdrawal and antisocial behavior and traumatized them for years to come. However, it is unfortunately necessary that infection-control protocols continue to be followed, as that will reduce the pandemic’s final death toll, reduce opportunities for new rogue variants of the virus to rise and ultimately end the protocols faster. The future of this outbreak is in everyone’s hands, and those with autism and special needs are watching closely.

Erin Polich • Mar 2, 2021 at 6:02 pm

Thank you for sharing. Since the lockdown I’ve also experienced a plummet in my mental health. I’m currently setting up appointments for an evaluation for ASD. Reading about others experiences helps a lot and makes it all a lot less scary.

Anna • Mar 1, 2021 at 12:14 am

Amazing article, Jacob! You have such a great voice and I can’t wait to read more of your articles!