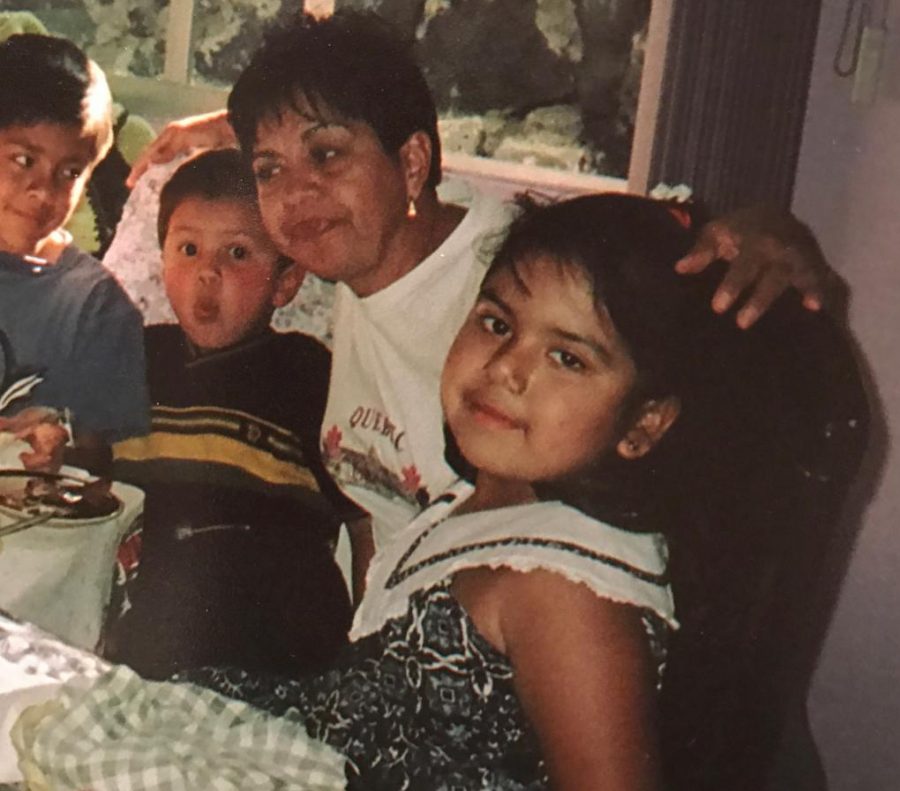

Courtesy of Jocabed Aragon

Jocabed Aragon, as a young girl

UNCW student’s experiences as daughter of immigrants, friend of DACA recipient

Jocabed Aragon is a senior at UNCW, a daughter of a previously undocumented Mexican immigrant, and a translator who works directly with hopeful immigrants to the United States.

In the concrete basement of an old church in Berkeley, Calif., a young woman in a t-shirt and jeans sits in a makeshift room at a small desk. On her left sits a woman in a long brown maxi skirt, who describes in detail the worst things that have ever happened to her. It is Jocabed Aragon’s job to listen.

The woman spoke in Spanish while Aragon, a bilingual college student from UNC Wilmington, translated it to English. This is called an intake interview. Such interviews aid Latin American asylum seekers in demonstrating that they are legally qualified to apply to stay in the United States.

Over the summer of 2016, Aragon worked with the group Jesus, Justice, and Poverty Institute, which provides these services for free. She was tasked with recording why these refugees came to the United States and determining the strength of their legal argument for staying.

The woman in the long skirt was calm as she described fleeing her home country in Central America after being extorted for money by a local gang. When she could not pay the $10,000 that was being asked of her, she was threatened. Members of her family were killed, and she was awakened in the night and raped in front of her infant child. With a numb expression in her eyes, she outlined it all to Aragon in gruesome detail. If she is not thorough, she may be sent back home, and she does not want that to happen.

As Aragon listened, she did not cry, not because she was not moved — she will remember this story for years and will tell friends back home — but because she needed to remain objective. She would not allow her emotions to be the thing that keeps this woman out of America.

The basement where they sat simply “looked like a basement,” in Aragon’s memory. It was a concrete, partially-finished space divided into rooms by loose plywood boards that had been installed by volunteers. The room where Aragon conducted most her interviews was lit by only a single bulb, and she would sometimes spend the entire day there translating written interviews or talking to people directly.

Her morning had begun in a small room shared with four other people. She got up and dressed simply. Most of the people she met with had nothing so she did not like dressing fancy. When she woke up, she prayed for the people she would see that day. She prayed that she would be able to help them and that she would not have to send any more away.

At the end of the day, Aragon left with Cynthia and Justin, a young couple, who comprised two of the four people with whom she was sharing a room. They all climbed into a silver Toyota Camry and drove home in silence.

Some nights, Aragon would go with Cynthia and Justin to a local bar to sit and talk about the people they met that day. They would exchange stories, not quite knowing what else to say.

Aragon remembers not crying. She had already done her crying. She said cried when her mother gained citizenship, and before that, she cried when her mother gained residency. And in a different way, she cried before that at all the times she thought something might happen to her family, causing her mother to be taken away to a country that Aragon had never seen, all because of rules she had been too young to fully understand at the time.

“I remember every stage. The stage where she was undocumented, the stage where she got residency, the stage where she got citizenship,” Aragon said.

Her father had become a citizen through the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, which granted citizenship to all immigrants present in the US before 1982. Her mother was still in Mexico City at the time, however, so she was forced to undergo a ten-year process of applying to be a citizen through marriage.

When she sees immigrants and asylum seekers struggling to find a safe home for their families, she said she cannot help but feel for them and remember what her mother went through.

“I lived that, personally not knowing whether my mom would be deported the next day and I would never see her again,” she said.

“When she got citizenship, I was 10…the ceremony was going to happen the day before my birthday,” she said, smiling as she recalled how relieved she had been after that day.

The ceremony was in a large convention center that required an hour of driving for her family to reach. The center was packed, and the Aragon family was tense. Jocabed and her mother both recall being worried that somehow it was too good to be true, that although she had studied all year and passed her test, Mrs. Aragon may still be denied citizenship.

Mrs. Aragon came to the United States as an experienced pharmacological chemist after having worked for drug companies straight out of university. When she came to the states, however, she was undocumented and could not get a job as a simple lab technician.

She worked any job she could find, but until her application process went through, she could not have a social security number and could only support her family by working under the table. She was mistreated and at times was denied pay by employers who would lie and say she had been lazy or she simply had to wait another week to receive pay.

Mrs. Aragon said she hated her early years in America. She missed her old life and her family. She could not travel for risk of being unable to return to the United States, and she spent ten years without seeing her sisters or any other family. As a result, she became severely depressed, especially at Christmas, she said. She desperately wanted to go back to her old life, but she said that she knew opportunities for her daughter were better in America and that she would rather be miserable than pull her child away from everything she had ever known.

But now, after ten years, she was officially a citizen. After the ceremony, she ran out toward her daughter, waving a tiny American flag and saying, “I’m American!”

It was a scene reminiscent to five years earlier when Mrs. Aragon received legal residency and was overjoyed that she no longer had to fear travel. The family did not have much money to spare, but Mrs. Aragon said that if she had needed to go into debt, it would be worth it to see her sisters again. The entire family left the very next week to visit the parts of Mexico where both of Jocabed Aragon’s parents had lived and met.

Aragon’s parents on their first trip to Mexico after Jocabed’s mother became a legal resident

Her favorite part of the trip was being in Puebla, where her father’s family was from.

“I had heard that I had a huge family, but it didn’t resonate,” Aragon said. “I have a small family here in the U.S., so that’s all I knew.” Being surrounded by her family’s culture was amazing to her, and although she was only five, what she saw on that trip would stick with her into adulthood.

She remembers being in Puebla on that first trip, standing in front of the multilevel home where her father’s relatives all lived. According to Aragon, it is traditional to build onto existing homes when someone is born or comes of age in Puebla, and the building continues to grow with the family. Standing there as a little girl on her first visit to a place that felt like home, she said she could not help but think how she will never get to be one of those additions.

“The way she talks about Mexico, the way she talks about her family, about our culture. Not everybody speaks up there,” said Argon’s friend Alondra Gutierrez, who was born in Mexico but was brought to America as a child where she now works through DACA.

“Joca. She’s the best friend ever. She really is,” Gutierrez said, remembering the day it was announced that DACA was to be repealed. “She messaged me, like, right after I got out of work and asked me how I’m doing and if I saw the news.”

“It’s people like her that give me so much hope. There’s still people out there ya know? That don’t think of us as criminals for coming here. They actually believe we’re here to support ourselves and our families. And that’s all we’re trying to do,” said Gutierrez.

“She’s very authentic in her lifestyle,” she said in reference to how Argon prioritizes cultural food and music. “Jocabed works so hard. She saw her parents start from nothing and get to where they are today. And that’s what gives her motivation. She knows we all start from nothing to get where we are. She knows the struggle. She might not have been born in Mexico, but her parents were, and she has seen them struggle. She was basically born there, too.”

“I do consider myself privileged,” Jocabed Aragon said while discussing her desire to use the small bit of privilege she has to help others. “Compared to them I was very privileged. And I was educated. Some people didn’t even know how to read or write because they were indigenous groups,” she said recalling people she helped over the summer.

“Even though she is a U.S. citizen, she acts so humble, so humble,” Gutierrez said in reference to how she was teased as a kid by other American-latinx kids who were citizens, but never by Aragon. “And it’s amazing. She talks about Hispanics with so much pride. She considers herself Mexican, even though she’s not.”

Aragon wants to devote her life to seeking social reform.

“I wish I could give them legal status. I wish I could give them my privilege in order for them to be okay,” she said.

Aragon is graduating from UNCW this year with a degree in intercultural communication studies and documentary filmmaking with a focus on cultural critique. Over the summer, it was her job to listen to the stories of immigrants like her parents, and for the rest of her life she wants to make it her job to tell those stories.