Beyond the Horizon: Colby Parsons blends technology and ceramics in new CAM exhibit

April 6, 2017

An exhibit at Wilmington’s Cameron Art Museum called Beyond the Horizon focuses on our relationship with landscapes. Contemporary artists Teresita Fernández, Maya Lin, Jason Mitcham and Colby Parsons are all featured in the exhibition which explores human connections to the ever-changing world. Employing various mediums, these artists challenge, examine and redefine the concept of landscapes.

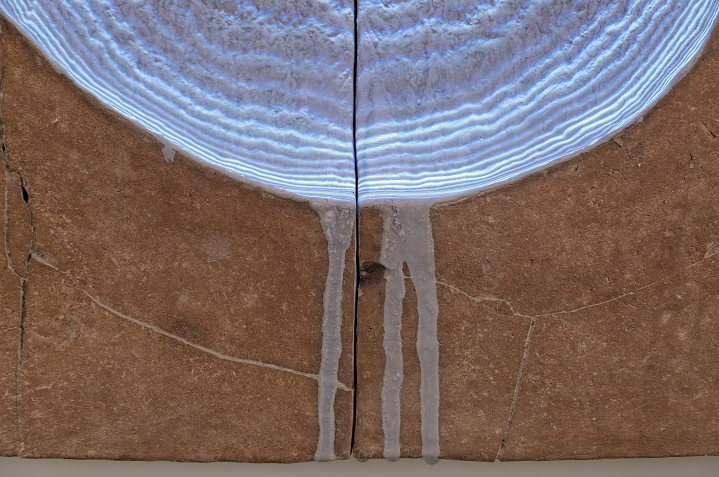

Artist Colby Parsons discusses his contributions to the exhibition, three separate pieces titled “Declivity #1,” “Landscape #1” and “Landscape #2” from his Materiality of Light Series. Parsons is a sculptor and professor of ceramics at the Texas Women’s University in Denton, Texas. His works explore the alteration and textural qualities of video projections in intersection with clay.

SHK: Your work cannot be fully captured in a photograph because of its moving aspects, how would you describe it to someone who has not yet seen it?

CP: Basically, the work is clay with video projections, and what’s projected on it are moving straight lines. Any kinds of patterns happen from the angle of projection, and so these works end up being unique each time I install them for an exhibition.

I think people can see for themselves what [the work is] doing. It’s not pinned down in a way where you get tired of it and that’s so interesting to me. I’m really interested in work where new technology, the projections, makes something possible and something traditional, the clay, makes something else possible, and then those two things work together rather than oppose each other. There’s a little bit of resistance among some people toward using new technology rather than just staying with all hands on, and I think in a lot of cases people think of clay in particular as a sort of antidote to technology.

SHK: How did you end up becoming a sculptor who also works with projection technology?

CP: In my undergraduate I had originally intended to be a graphic designer, but I thought of myself more generally as an artist. Eventually, like most college students, I ended up changing my major. I threw myself into whatever class I had and it just turned out that I felt like there was more I could explore within ceramics, so ultimately I majored in that.

SHK: Mixing clay with technology is not necessarily a commonplace form of mixed media. How did that come about?

CP: As a kid I always really wished I had a camera to do animation, but it cost too much at the time. About fifteen years ago I thought, “Wouldn’t it be interesting to take a mostly static medium, and these new emerging technologies, and bring some kind of movement to it?”

Then I thought, “What if I could show that as an animation?” Not like Claymation, like Wallace and Gromit, but things like fired clay. I wanted to take the qualities of fired clay and make those end up in the movement. So I started making these series of small animations, but eventually I wanted to be able to show them in a way that was bigger than just on TV. That’s when I got the projectors and started the work, which was kind of difficult in 2002-2003.

I was in between functional and sculptural for a while, and it was in grad school that I shifted over to making sculpture and incorporating multimedia elements, sometimes stuff like wood or asphalt. It was after, when I was working as a professor, that I ended up incorporating the digital elements that you can find in this series.

SHK: What is it like working with the projectors now, considering that you began working with them in the early 2000s?

CP: Projectors were starting to be around then, but they were so expensive not many places had them. I think the first projector I bought was in 2004, and compared to now it was a decent amount of money. Now I can run out to the store and get a quality projector for just a couple hundred dollars, so that’s been a big change.

The way I think of [the projections] is like it’s a spotlight where I can control every dot of its output, and so it’s like you can paint with it, design with it. And that’s the approach I take. I make the projections myself, and I always have to adjust them. I’m always working to find new things I like about the projections themselves. When I show the work, it’s a little different every time. I like that about [these pieces].

I’m getting into 3-D printing now, and the people doing exciting things with 3-D printing, for me, are the ones who are messing it up and making it print in ways that look kind of not clean and pristine, but maybe show all the lines and textures. So the equivalent of those things on a projector is this thing that projector companies try to avoid called “the screen door effect.” Really, at this point, projectors don’t show that, but 5-10 years ago they hadn’t gotten to the point where they were hiding it yet. So I use that, I point it at an undulating surface and get this sort of topographical map equivalent. All the lines of pixels articulate and stretch around the form.

SHK: What about the ceramics aspect?

CP: I feel like in ceramics in general we teach people to look for the ways in which flaws can become aesthetics, for the way the qualities of the material can become kind of the main asset of the work. Of course, that’s not true for all work, but it’s something I enjoy embracing. If I’m involved in a new process, I’m looking for that, for the messy thing it isn’t supposed to do.

SHK: Were there any specific methods or techniques going into making any of these pieces on the ceramic side of things?

CP: Interestingly enough, I actually got [“Declivity #1”] out of the kiln and felt like it was a little too plain in some way. So I just started smashing it against the ground and breaking it apart. Then I used kiln mortar to put the pieces back together. I love that about [that] piece, that it’s got these places where it looks like these geologic shifts and occlusions.

SHK: The lines projected on the piece move continuously. Do you create them the same way each time?

CP: The lines are just straight lines. What’s going on is there are many many different layers of stripes with different opacity that are moving at varying rates, and the rates change. There are points where you’ll see a secondary pulse run through it where the lines are overlapping one another and they aren’t exactly the same.

I basically have a few different techniques I developed where I layer those. I try a few of them out, and when one of them seems to work with a particular piece, then I work to add enough complexity that if you stand there for a little while it’s not like after 10 seconds you’ve seen everything it can do.

SHK: Aside from the clay and the projections, are there any other aspects of the work you feel are very individualized to you as an artist?

CP: I spent a couple of years developing this glaze, it’s specific for video. It’s a micro-crystalline glaze, so it has all those tiny little sparkles from those just barely visible crystals forming. I like that because it’s got that silky texture. It’s one of my favorite kinds of glazes. These kinds of glazes run a lot, so that’s something I’ve embraced here as well. You can see that aspect of the work in “Declivity #1.”

SHK: Your piece “Landscape#2” can give the impression of a human body lying down from the right angle. Was this intentional?

CP: I think there’s this sort of subconscious thing where the kinds of things we have associations, about what seem tactile, are the same things we have associations with sexually or sensually. I don’t think it’s an accident that some of my pieces end up looking like body parts because that sense of what’s pleasing as a visual flow relates to other kinds of experiences. Some people say things like, “oh that’s the breasts and butt piece” about “Landscape #2,” but I do think that abstractly it is more figurative than any of the other pieces like this.

SHK: What is something that gets overlooked about this series?

CP: I think some people don’t realize when they see this kind of technological stuff how much hands on, what I would consider craft, is involved. So I’m here crafting the way this line is, and if I do it one way it gives it a certain look, and if I do it another way it gives it a completely different look. It’s that attention to detail that makes this have this almost magical quality, like the light is coming from the inside of it. To me, that is what makes it ultimately work.

You can find Beyond the Horizon on display at The Cameron Art Museum until July 9 as well as their other exhibition celebrating the studio glass movement’s 55th anniversary, From the Fire, on display until Aug. 11. Seniors, active military and students can present their I.D. during ticket purchase to receive $2 off the $10 entry fee.